WHAT IS THE MARITIME DIMENSION OF THE WAR IN GAZA, FROM THE RED SEA TO THE INDIAN OCEAN?

May 30, 2024

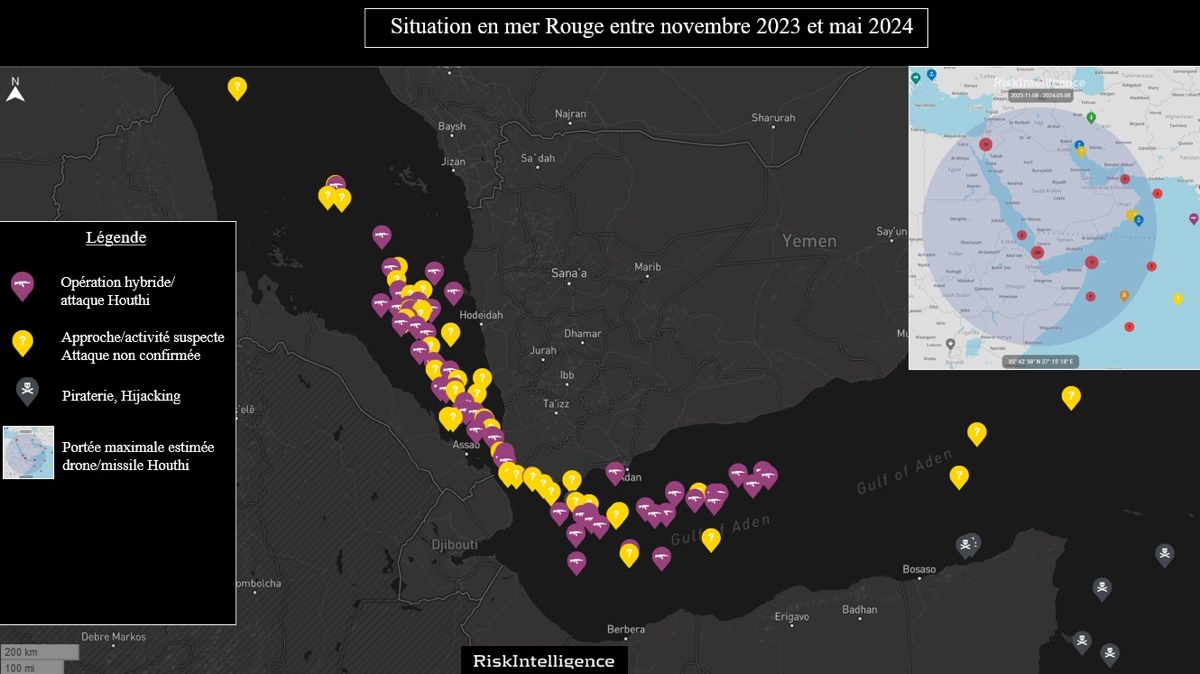

The authors provide a documented picture of the situation in the Red Sea and then in the Indian Ocean. They then study the possible causal links between the Houthi attacks in the Red Sea and the renewal of pirate attacks in the Indian Ocean. Which illustrates, against the backdrop of the war in Gaza, in the land/sea interdependence, the chaos of scales and the interconnection of the crises of the present time. Two unpublished maps illustrate this article.

THE maritime IMPLICATIONS of the Hamas attack on October 7, 2023 only became apparent after several weeks of conflict. In order to analyze the state of the threat according to the areas considered, a brief overview seems necessary, the war between Hamas and the Tsahal being the cause of the extension of the current conflict in the Red Sea. Indeed, according to their official speech, the Houthis will continue their actions against ships passing through the area as long as Israeli operations continue in Gaza. If the objective is to harm Israeli interests, Israel and its maritime facade in the Eastern Mediterranean have nevertheless remained relatively spared on the maritime level [1].

However, with the entry of the Houthis into the war, the conflict changed geographical scale, shifting from a regional dimension to a global logic, by directly threatening ships transiting in the Red Sea, between the Bab el-Mandeb Strait [2] and the Suez Canal, two strategic thresholds essential to the free movement of a globalized and maritime economy, and through which 30% of the volume of containers (15% of world trade) transits. Among these first collateral victims are the Suez Canal, which announced a drop of almost 50% in its revenues and 37% in the number of passages. Most shipowners, led by MSC, Maersk and CMA-CGM, prefer to bypass the Red Sea via the Cape of Good Hope, a detour of 6,000 km implying a significant increase in freight rates.

Since geopolitics abhors a vacuum, the operational and media call created by the conflict in the Red Sea has abandoned the Indian Ocean, where pirates have been rampant again since the end of November 2023.

By providing a general picture of the situation in the Red Sea (first part) and in the Indian Ocean (second part), the objective of this article will be, in particular, to study the potential causal links between Houthi attacks at sea Red and pirate attacks in the Indian Ocean.

Once the geographical spaces have been delimited, it is necessary to identify the type of actors and threats to which civilian ships and military vessels deployed in the area are exposed. Thus, it is important to distinguish Houthi attacks [3], a pro-Iranian paramilitary insurgent group motivated by political, strategic, symbolic and media objectives targeting Israeli interests and their allies, from pirate attacks – whose modus operandi differs greatly – motivated by the lure of gain, and seeking the most favorable gain/risk ratio possible. Terrorist groups play a different role in this equation. The Qaidist group Al-Shebbab plays an indirect support role for pirate groups in Somalia. While the leader of the Houthi rebels, Abdul-Malik al-Houthi announced in mid-March 2024 his intention to extend his attacks towards the Indian Ocean, therefore in an area close to piracy zones, these distinctions are all the more important.

Red Sea: situation update

The Houthi campaign against maritime trade in the Bab el Mandeb Strait is now entering its sixth month, and things are looking good for the Houthis. Western military pressure has failed to prevent the Houthi quasi-state from carrying out its strikes in the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden. The diplomatic route seems ineffective, when it is not counterproductive.

In November 2023, in response to the Israeli offensive on Gaza, the Houthis announced that ships with a real or perceived affiliation with Israel would potentially be targeted if they crossed the Bab el Mandeb Strait or the Red Sea, specifying that their targeting would last as long as Israel conducted ground operations in Gaza. This resulted on the ground in a succession of missile and drone strikes against maritime targets, which began with the spectacular seizure of the Israeli leader ship Galaxy off the coast of Yemen in November 2023.

While the Houthi campaign initially focused on Israeli commerce, the number of “acceptable” targets for the Houthis was gradually expanded to include the majority of Western commercial vessels, perceived as allies of the Israelis. After five months of the campaign, maritime traffic through the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait and the Red Sea has fallen by 50% compared to its level last year.

In response, two naval coalitions largely led by the West (and in particular the United States) were formed. The first, Operation Poseidon Archer (OPA), was tasked with carrying out strikes on Houthi territory while Operation Prosperity Guardian (OPG) was tasked with escorting civilian ships through the strait, to which adds the European operation Aspides with a similar mandate.

These limited armed operations offer no prospect of a diplomatic or military resolution at the end of May 2024. The British and Americans strike Yemen, without producing significant effects on Houthi strike capabilities.

What do the Houthis gain from attacking maritime trade, and by extension from alienating part of the West? The answer lies in the Houthis’ self-perception and interpretation of the world. The Houthis are a small clan from northern Yemen, originating from Sa’ada, on the border with Saudi Arabia. The members of the clan consider themselves legitimate to rule over “their” Yemen, which corresponds, more or less, to the territory of the former Republic of North Yemen, dissolved during its reunification with South Yemen in 1990. Intimate enemies of the Saudis, the Houthis led, well before the 2015 war, numerous skirmishes against Yemeni and Saudi forces.

Nine years after the successful insurgency, the Houthis find themselves in a favorable position. They dominate North Yemen, and consider themselves the victors in a Western war waged by proxy. This perception is supported by a long list of military and political successes. Indeed, the Houthis survived [4] eight years of Saudi and Emirati bombings, described as Arab puppets of an imperialist West. The experience acquired by the Houthis throughout these Arab bombardments allows them today to attenuate the effectiveness of Western strikes. This political victory for the Houthis places them in a position of strength not only against the Saudi adversary, but also against the West [5].

The military option having failed, and the West having long since indicated its refusal to recognize a “Houthi Yemen”, the Houthis took advantage of the absence of leverage available to their adversaries, devoid of any desire for plausible projection.

In the context of the post-October 7, 2023 crisis, the Houthis and the Iranians were able to reach an agreement to launch an anti-Israeli campaign. If, fundamentally, it is the animosity between Iran and Israel that pushes actors in the Iranian orbit to strike “Zionist” targets, the Houthis certainly saw this as an opportunity to advance their own pawns.

First, the operations carried out by the Houthis reinforce their role in their alliance with the Iranians, who depend on their proxies to conduct actions across the Middle East. This campaign should guarantee the Houthis continued support from the Iranians.

Then, the Houthi campaign makes it possible to legitimize their position and generate significant popular support among the Arab populations, most often Sunnis, largely committed to the Palestinian cause.

Furthermore, this campaign contributes to weakening Saudi power, and confronts Arab leaders with their contradictions. Self-proclaimed protector of Muslims, Saudi Arabia [6] can hardly ask the Houthis to stop their military reaction to Israeli operations.

Finally, engaged in a struggle with South Yemen for control of trade flows, this demonstration of power reinforces Houthi control over maritime trade [7] around Yemen.

Where is the blockage?

Paradoxically, it is the prospect of peace between Saudi Arabia and the Houthis which perpetuates hostilities. After eight years of conflict, the Houthis and the Saudis signed a ceasefire agreement, and complex negotiations are still underway in early May 2024, complicated by the Houthis’ notorious maximalism and the Saudi reluctance to negotiate from a position of weakness.

Saudi Arabia, which considers Yemen its private preserve, wishes to negotiate a “comprehensive peace” for Yemen, preserving the contours of a united (and divided) Yemen. The Houthis are only negotiating a peace between themselves and the Saudis, whom they know are impatient to end a war they no longer want. The April 2022 ceasefire, which put an end to mutual strikes, forms the basis of these negotiations. Their failure would mean a return to the violence before 2022, and dramatic consequences for the Saudi project of diversifying its economy, requiring a stable environment in order to attract foreign investment.

The Saudi policy of “stabilization at all costs” of its neighborhood, unusually short-term for the kingdom, leads it to pass their excesses on to the Houthis. The Saudis do not condemn the Houthis when they fly missiles over their territory to strike Israelis. This highlights Saudi Arabia’s political dilemma given the arsenal of anti-missile batteries deployed along its 1,800 km of Red Sea coastline, specifically to counter strikes from Yemen. The official Saudi press no longer considers the Houthis to be terrorists, and is no longer outraged by skirmishes on its border with forces of Houthi allegiance. Above all, the Americans, wishing to preserve their relations with the kingdom which continues to emancipate itself from the American strategic umbrella, no longer dare to press the Saudis on the Yemeni question, for fear of accelerating the disintegration of a much less established alliance. strategic than before.

Black gold

The disintegration of historic alliances in the Middle East, against the backdrop of a more global strategic realignment, has created a security vacuum which the Houthis are exploiting.

The Middle East and the United States are no longer essential to each other. The American shale gas boom (which is coming to an end) has diverted the leading economic power from the Middle Eastern market, while the American “pivot” towards Asia and the war in Ukraine are Washington’s new priorities. At the same time, the Gulf now exports more than 70% of its gas and oil production to Asia (especially China), which is not associated with the conflicts in the Middle East, and which, with the exception of Singapore has no particular sympathy for Israel.

It is therefore not surprising that it was China, the main client of both Iran and Saudi Arabia, which negotiated a de-escalation agreement between the two regional rivals in March 2023. The Gulf petromonarchies depend now from Asia [8] for their income and are therefore more sensitive to their interests. It is in this global context that we must understand the Houthi announcement that vessels affiliated with Chinese interests would not be targeted. Russian ships also benefit from Houthi leniency thanks to the Russian alliance with Iran and China, the main customer of Russian oil. Furthermore, American retreat from the region has not been compensated by the appearance of an equivalent security actor, with China having neither the means nor the will to take over the role. As for the regional powers, they present no credible means in the face of the Houthi threat.

The Houthis are seizing the opportunity created by this security breach, with no state actor willing to engage in a new conflict in the Middle East. A land invasion of Yemen would temporarily stop maritime attacks, but would not provide a lasting solution, while the prospect of stopping operations in Gaza does not seem to be looming in the short term.

The Houthis do not seem inclined to compromise the strategic interests hitherto protected by national sovereignties. In this reading of the facts, the Houthi attacks remind us that the status quo in the Middle East is not a lasting option.

Against the backdrop of the war in Gaza, land/sea interdependence, the chaos of scales and the interconnection of the crises of the present time.

Indian Ocean

If all eyes are rightly turning to the Houthi attacks in the Red Sea, the Gulf of Aden and the Indian Ocean are also the site of an upsurge in piracy attacks since November 2023, a first in 4 years , the previous confirmed attack dating from April 2019 [9].

The first type of piracy, located near the Somali coast, would certainly be linked to Illegal, Unregulated, Unreported (IUU) fishing activities. A disagreement between Iranian fishing vessels and the company based in Bossasso which administers fishing licenses is believed to be the cause of the first attacks observed in November 2023, which is why many of the pirated dhows and fishing vessels are under the Iranian flag, as Al Kambar or Al Miraj, diverted off Bossasso. Piracy activities would then have spread to other vessels, notably Yemeni, considered to be engaged in illegal fishing activity, totaling around ten attacks reported between November 2023 and April 2024, linked to fishing disputes. Other incidents, such as that involving the fishing vessel Najm on March 16, 2024, are believed to be more linked to internal disputes.

The second type of piracy is much more daring and professional, and the attack on the MV Ruen on December 14, 2023 is in this context interesting to study. The first successful hijacking of a commercial vessel by Somali pirates since 2017 [10], this affair could have marked the return of the golden age of piracy of the years 2008-2012. As a reminder, the Ruen, a bulk carrier flying the Maltese flag, was attacked by Somali pirates from a fast boat, before boarding the ship and diverting it to its place of detention, an anchorage off the coast of Bander Murcaayo, in Puntland. Before its release on March 16, 2024 by the Indian armed forces deployed from the frigate INS Kolkata, leading to the arrest of the 35 pirates and the release of the 17 crew members, the Ruen could have served as a cursor to determine whether the Piracy was once again becoming a profitable business, in a context of the end of the monsoon period, and international attention focused on the Red Sea leaving pirates with a certain permissive and maneuvering space. Through this attack, the pirates demonstrated that they maintained their skills and their appetite to carry out attacks on the high seas, more than 430 nautical miles from the coast. Different sources suggested that the Ruen may have served as a mothership to carry out raids against other ships in the region, such as the MV Abdullah [11], hijacked on March 12, 2024 and released a month later, but this hypothesis seems unlikely due to the fact that the MV Ruen was tracked by the Indian Navy, which was subsequently able to carry out its recapture operation by force once the vessel left Somali territorial waters.

In this context, the situation on land is also important to take into account. In the coastal region of Bari, off which the MV Ruen, then the MV Abdullah [12], were kept at anchor, it is probable that these operations were made possible following an agreement with the Shebbab, which would let operate the pirates in return for the payment of part of the ransoms, estimated at 30%. As for them, pirates can carry out their raids and benefit from weapons from the Shebbab arms trafficking networks.

The pirates have also retained their know-how to carry out long-range attacks, demonstrated during the attack on the bulk carrier Waimea 764 nautical miles from the Somali coast on January 27, 2024. Raids beyond 200 nautical miles are carried out from a mother ship, certainly from dhows hijacked a few days earlier. On the high seas, the most likely scenario is therefore that of pirates operating from mother ships searching for targets, waiting for favorable sea conditions, and in areas far from potential naval patrols. According to estimates from RiskIntelligence and MSCHOA, and taking into account the distance separating the attack zones, it is likely that two to three pirate groups are operating on the high seas. This was, for example, the case during the attack of the trawler Lorenzo Putha 4 on January 27, 2024, hijacked approximately 840 miles east of Somalia by a pirate group operating further south, when another group attacked further north, requiring intervention by the Indian navy of Lila Norfolk 460 nautical miles from Somalia.

If there is no direct causality between the increase in pirate attacks and the crisis in the Red Sea, it is nevertheless possible that certain pirate networks have been reactivated to take advantage of the attention given to the Red Sea, thus abandoning the Indian Ocean, whose resources deployed by EUNAVFORAtlanta [13] – which celebrated its 15th anniversary in November 2023 – and CTF 151 were already reduced.

Other factors are likely to come into play in this upsurge in attacks. If the maritime industry continues to play a central role in following the Best Management Practice (BMP5), the vigilance of crews has been able to lessen with several years without a successful pirate attack, then the withdrawal of the High Risk Area (HRA) status. of the area by the International Maritime Organization. Furthermore, in the interests of economy, the deployment of Private Contracted Armed Security Personnel (PCASP) was less systematic.

Taking into account the call for air in the Red Sea and the establishment of energy-intensive operations in means Prosperity Guardian, launched in December 2023, and the European mission Aspides, launched on February 19, 2024, India [14] seized the opportunity to establish itself as a major regional security player and to play the role of policeman of the ocean [15] which bears its name. In addition to the opportunely seized opportunity to assert its presence, these anti-piracy operations also allowed New Delhi to demonstrate, with extensive communication [16], its operational and legal know-how. Indeed, India deployed a major device in the area as part of Operation Sankalp, which made it possible to carry out complex hostage release operations in short periods of time, involving Tarpons (parachuting into the sea of special forces ) 1,400 nautical miles from the Indian coast.

At this stage, it is still early to assert a return of the golden age of piracy in the Indian Ocean. The maritime industry is already prepared, the Combined Maritime Forces (CMF) structured and deployed, as well as the structures participating in the sharing of maritime information [17]. The Indian Ocean, however, remains a major area of vigilance, the fate of which remains linked to developments in the situation in the Red Sea.