In the heart of the Pacific, Easter Island sees millions of plastic waste items wash up on its shores every year. This small Chilean territory also has to deal with the trash left by tourists who come to admire its iconic statues.

In Hanga Nui, on the southeastern tip of Easter Island, 15 Moai statues are lined up side by side. Tourists, phones in hand, take photos of these giant stone statues, which in the Rapa Nui culture represent important ancestors of the tribes that once inhabited the island. A few hundred meters behind this postcard view, another panorama unfolds.

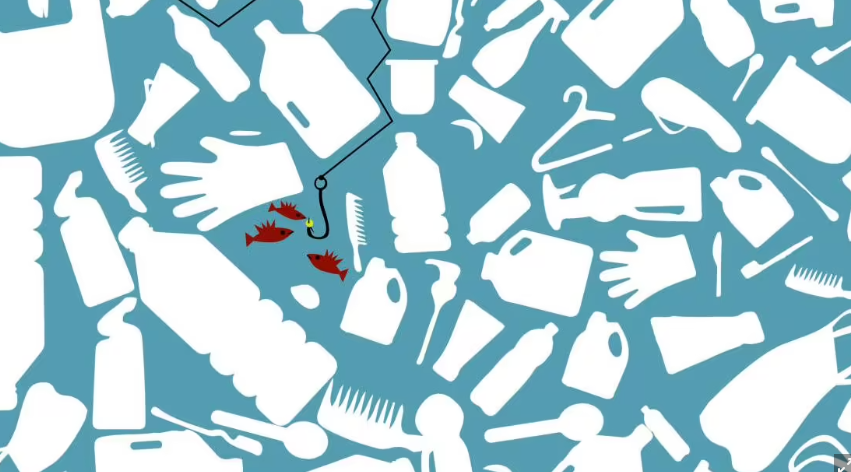

On the shoreline, sitting between the rocks, Kina Paoa has her hands buried in the sand. The 22-year-old woman, born on Rapa Nui, collects hundreds of small colorful confetti pieces. It’s actually plastic. The more she digs, the more she finds: « The vast majority of this plastic comes from other countries and arrives here via the sea, » she explains. Easter Island is located in the middle of the South Pacific Gyre, a powerful swirling current that brings 4.4 million pieces of waste to its shores each year, according to a study by the Northern Catholic University in Chile.

« This plastic has been traveling in the ocean for so long, with the sun, the salt, and the impacts against the rocks, that it eventually breaks down into tiny pieces, » Kina continues. She also finds tires, buoys, ropes, bits of buckets, plastic caps, and polystyrene boxes washed up among the rocks. « Each time we go out, we collect about 20 to 30 kilos of garbage, » she adds. It was during a marine conservation workshop in middle school that Kina first became interested in this plastic scourge. Now, she goes to the beach every weekend to collect the waste that constantly washes up on the shore. She then transforms the plastic in her workshop into small objects like keychains, candle holders, or dominoes, which she sells to tourists. « I still feel like it’s not really helping because it’s impossible to collect all the plastic. After spending three or four hours cleaning the beach, there’s always more left, » she laments.

Beside her, her cousin Maria José Paoa walks around and returns with her arms full of plastic pieces and ropes. « I feel more at ease after cleaning the beach, » she says. But she adds, « It’s very impactful to see the amount of waste we collect. Sometimes it’s depressing. I spend hours and hours of my life collecting trash that’s not mine! At the same time, there are other places in the world where none of this matters, and they keep generating more and more waste… Sometimes, I start thinking and I tell myself that my efforts are insignificant. »

Plastic in their stomachs

In the waters surrounding the island, there are reportedly over a million microplastics per square kilometer. Almost all native fish are contaminated with microplastics or invisible nanoparticles in their bodies. Carlos, a fisherman who just docked his boat in the small port of Hanga Roa, attests to this. As he empties the ten tuna he has just caught, he says, « My parents and grandparents didn’t find plastic in the fish, unlike me today. Sometimes, I open the fish, and there’s plastic in their stomachs. Turtles can also get trapped in it, and we need to intervene to free them. » He believes that a significant portion of the waste reaching Rapa Nui comes from industrial fishing boats, which are abundant in the international waters around the island.

“My parents and grandparents didn’t find plastic in the fish, unlike me today. Sometimes, I open the fish, and there’s plastic in their stomachs,” says Carlos, fisherman. — © Bela Jude for T Magazine

Nancy Rivera, who coordinates the marine investigation unit for the Rapa Nui municipality, agrees. She estimates that at least 50 to 60% of the objects that end up on the beaches are fishing gear. Her colleague, marine biologist Emilia Palma Tuki, confirms, « We found a buoy with numbers, like a registration plate. After some research, it turned out these numbers corresponded to a Chinese boat with available quotas for fishing. »

Japanese, Australian, and even European boats are also in the area. Pamela Averill, an oceanographer, remembers identifying the origin of fish crates based on markings on their packaging: « Many indicated Spain. » She also notes that some of the plastic deposited by the waves on the island’s shores comes from South America, especially from Peru and Chile, over 3,500 kilometers away. While it is difficult to trace the origin of all this plastic due to its degradation in the sea, one thing is certain: « In the last fifteen years, there has been an exponential increase in waste on Rapa Nui, » says Pedro Lazo Hucke, a park ranger on the island. He points to the responsibility of the countries that produce these waste items and believes it is up to them to establish recycling systems or even stop producing plastic altogether.

Cleaning Sessions

Regularly, the Rapa Nui municipality, assisted by locals, organizes beach cleanups to collect the waste that accumulates on the shores. The waste is then brought to the Orito recycling center, where it is piled into large bags. « We have no other place to put it, » regrets Alexandra Tuki, who has managed the center for over twenty years. « They stay here until we find staff to sort them. It’s better that they are here rather than on the shore. » At the entrance of Orito, stray dogs lying on the ground avoid the trucks unloading kilos of plastic bottles, aluminum cans, and other cardboard near the hangar that houses a large compactor. The recycling center mainly deals with domestic waste produced on the island by its approximately 8,000 residents and also by the many tourists.

The thirty employees manage to recycle just over 5% of the island’s waste. « It saddens and frustrates me to see so much waste, » says Alexandra. « When I was born, there wasn’t as much. Unfortunately, today, we have a very consumerist mentality. » The island’s economy is entirely geared towards tourism. It receives over 70,000 visitors each year, fewer than before the pandemic but double the number from ten years ago. At the same time, waste production on Rapa Nui has increased. Each week, the Orito center manages to send ten tons of sorted waste to the mainland through an agreement with the only airline that operates on the island.

The island receives over 70,000 visitors every year, fewer than before the pandemic but twice as many as ten years ago. At the same time, waste production has increased. — © Bela Jude for T Magazine

Alexandra would like to do more, but she lacks financial, material, and human resources. The 95% of waste that cannot be recycled ends up at the municipal landfill, which is soon to be saturated, with scavengers circling in search of food. Tons of trash accumulate in the open air, with the intense blue of the Pacific Ocean as the backdrop. Alexandra points to a polystyrene crate abandoned among the debris: « These crates arrive by plane and contain fruits, vegetables, and frozen meat, » she explains. « It’s cheaper for tourist establishments to buy their products from the mainland rather than from local producers. »

Easter Island, however, aims to become a « zero waste » territory by 2030. The municipality is implementing measures to help the tourism sector reduce its waste. Some of the Rapa Nui population has also gotten into the habit of recycling their trash. But with the continuous influx of plastic by sea and the ongoing production of domestic waste, this goal seems difficult to achieve for now.