Around Kerkennah, the sea has become a battleground where traditional fishing practices clash with the destructive modernity of illegal trawling. Behind this conflict lies the fate of the marine ecosystem and the very survival of local fishermen.

On the Edge of Tradition: Kerkennah’s Fishermen Battle Illegal Trawling

On the terrace of his waterfront home, tucked away at the end of a sandy path on the Kraten islet in northern Kerkennah, Neji spends the evening with friends. The day at sea was long, but tradition is sacred here: “I keep doing this job out of love for my culture and my family. But I’m not optimistic about the future.” The seasoned fisherman fears that if nothing changes, Kerkennah’s age-old fishing traditions will vanish. “Our children will have nothing left to live off from this sea,” he says.

In Kerkennah, the “Charfia”, a traditional fishing technique passed down through generations, is a cultural gem. But in recent years, informal trawlers have invaded these waters, using a method locally called “Kiss”, which destroys the seabed and dangerously depletes fish stocks.

Caught between ancestral traditions and growing environmental threats, Kerkennah’s fishermen are fighting to preserve their way of life in a sea now at the center of a struggle for control.

A Fragile Balance

The Gulf of Gabès alone accounts for 33% of Tunisia’s national fish production and harbors unique biodiversity. At the heart of this gulf lies the small Kerkennah archipelago, long sustained by its traditional fishing techniques. For generations, fishermen here have practiced the Charfia, a method inscribed on UNESCO’s Intangible Cultural Heritage list since 2020.

Neji prepares a red mullet stew, caught earlier that morning, while passionately describing the ancestral technique passed down by his family. “My grandfather was a fisherman, my father too. I’ve been fishing for nearly fifty years. It’s a way of life here, handed down from father to son,” he shares.

The Charfia relies on fixed traps made from natural materials like palm branches. These channel fish into capture chambers without harming the environment. This technique allows young fish to be released and keeps the ecosystem intact, preserving species continuity.

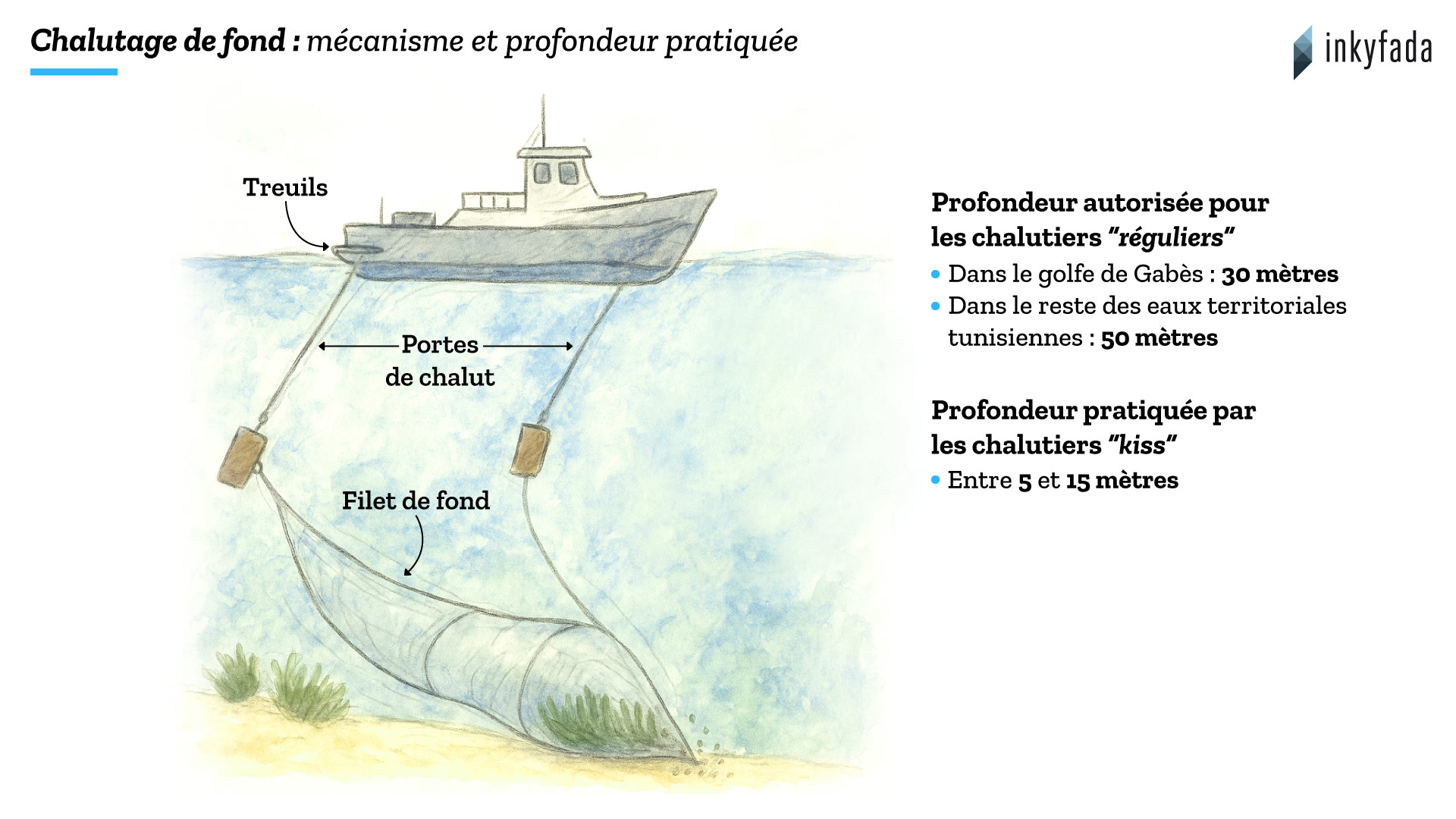

By contrast, illegal trawling—locally known as “Kiss”—involves dragging heavy nets across the seabed, destroying vital marine habitats and indiscriminately capturing all species. This intensive method, often used by unregistered boats, is believed to have emerged in the 1990s in Sidi Mansour, near the Sfax coast, before spreading to the Gulf of Gabès.

The use of Kiss increased dramatically after the 2011 revolution, amid a lack of enforcement and regulation. “When people saw that authorities weren’t confronting trawlers or penalizing what was already illegal, more and more fishermen adopted the practice,” says Ahmed Souissi, member of the Kraten Association for Sustainable Development of Culture and Leisure (AKDDCL).

Today, illegal trawlers operate in shallow waters between 5 and 15 meters deep—well below the 50-meter legal threshold for trawling.

In the Southern Waters of Kerkennah, Illegal Trawlers Dominate While Tradition Clings to Survival

In the southern part of the Kerkennah archipelago—referred to as “the West” by locals—ports like Sidi Youssef are now largely occupied by informal trawlers.

On this particular day, the boats are idle. The wind whistles between the hulls, blending the cries of seagulls with the heavy scent of diesel and sea salt. Sitting directly on the ground, fishermen hurriedly mend their nets.

« We’re left with debts and bills we can’t pay. Everyone is just trying to survive in this job, but it’s getting harder and harder, » says a fisherman working aboard a trawler.

In contrast, to the north—called “the East” by locals—artisanal fishing is still holding on. Traditional methods persist there, despite the mounting pressure from destructive practices.