The One Ocean Science Congress, held from June 4 to 6 in Nice, precedes the 3rd UN Ocean Conference (UNOC3) next week. Within this framework, the launch of several international initiatives – Ipos, Mercator, Starfish… – could mark progress in knowledge and action in favor of the vast blue under multiple pressures. Although not everyone shares this view.

Seafloor Mining: A Political Decision Awaiting Clear and Consensus Scientific Advice

The topic of seafloor mining—should we extract resources from the ocean floor?—is a textbook example of a political decision pending enlightened and consensual scientific guidance. Literally so: located in total darkness several thousand meters deep, these vast abyssal plains remain largely unknown and ripe for major discoveries. One notable finding, still debated, is last year’s discovery of « black oxygen » emitted by polymetallic nodules—these mineral-rich pebbles highly coveted by various countries and companies.

The draft declaration for the conference reminds us: “Action for the ocean must be based on the best available knowledge.” This conveniently broad wording avoids frustrating any ambitions. Yet, the key principles for the vision ahead are clear and better stated than left unsaid. Disturbing the deep sea without first measuring potential consequences—such as the release of sequestered CO2—could be a very bad idea.

“Scientific Pillar”

“Since the One Ocean Summit in Brest [2022], we have aimed to build UNOC from science,” said Olivier Poivre d’Arvor, France’s Special Envoy for the Ocean and Poles, a key figure shaping the Elysee’s narrative. “The political declaration of UNOC, currently negotiated before the conference, is ambitious scientifically.”

Indeed, the role of scientists at a UN ocean conference is unprecedented: it is the first time a scientific congress is directly linked to a UN ocean conference. About 2,000 scientists—mostly women—from 133 countries will participate in the One Ocean Science Congress (June 3-6), just days before the diplomatic segment of UNOC. Biologists, geologists, oceanographers, geophysicists, chemists, engineers, as well as social sciences, law, and economics experts—all disciplines are involved, since understanding the complex ocean requires multiple perspectives and combined skills.

“It’s fantastic; it identifies science as decisive in international negotiations,” says Françoise Gaill, marine biologist and emeritus research director at CNRS. “It’s huge,” adds her CNRS colleague Marina Lévy, “I’m very enthusiastic,” noting that “ocean science laid the foundation for UNOC.” “All the ocean’s threats will be discussed. They remain largely invisible, and if UNOC only helps make them more visible, that’s already a big step,” she believes. Both are leading major projects and deeply involved in the event.

Key Ocean Topics on the Agenda

The big ocean issues are indeed on the table: climate, biodiversity (marine protected areas), deep ocean and geopolitical challenges, genetic resources, fisheries and food systems, plastic pollution, decarbonization of maritime transport, knowledge sharing and tech capacity-building with the Global South… Nearly 500 oral presentations, roundtables, and public outreach sessions in the “green zone” are planned. Although the U.S. presence is reduced due to travel bans on NOAA and USGS researchers, about 150 Americans remain on the participant list.

The goal of this “scientific pillar” of UNOC3, according to François Houllier, president of Ifremer and of the Congress, “is to provide policymakers and society with in-depth expertise on ocean health, future trajectories, and ecosystem services.” Concrete recommendations will be made to heads of state, aiming to feed the political discussions occurring June 9-13 at the official UN meetings.

A Community Between Enthusiasm and Skepticism

“This moment will mark the recognition of science’s central role in policy preparation, implementation, and evaluation,” say the organizers. Françoise Gaill points out a key debate will be the relationship between science and politics. Some scientists are frustrated by the lack of concrete action despite available knowledge.

Jean-Baptiste Sallée is among them. “I don’t want to be a scientific alibi,” explains the CNRS physical oceanographer. “We have the knowledge. Of course, more science is needed to understand, but we know enough to take many measures.” Frustrated by the “double discourse” between words and actions, he and colleagues decided not to attend in Nice. “I see this as mere showmanship. France tends to position itself as a good international student. True, it often leads negotiations. But afterward, nothing happens nationally.”

He cites the classic example of marine protected areas: in France, 30% are theoretically protected, but only 1.6% effectively so—since destructive bottom trawling is still allowed. Julien Rochette, ocean expert at IDDRI, noted in a blog post that “France’s maritime and coastal policies are not always exemplary, and many voices rightly criticize the lack of ambition in marine protected areas, marine pollution from land-based activities, and numerous harmful subsidies degrading ocean health.”

A year ago, Sallée was among 260 scientists signing a sharp op-ed in Le Monde titled “Growing distrust in our scientific community toward political power.” “We have observed, like many citizens, the gap between announcements and (in)actions. After many disappointments, distrust grows,” they wrote, noting “all ocean and climate signals are red.”

Marina Lévy admits her enthusiasm for the Congress and UNOC isn’t shared by all. Interest among peers is “very mixed.” While she agrees the ocean is drifting, she sides with “those who say it would be worse if nothing had been done.” She only regrets the “negative narrative dominating. When people oppose, they speak out, while those positive about these conferences rarely do.”

Transatlantic Anti-Science Shockwave

The anti-science wave in the U.S., still ongoing, has shocked French partners and likely influenced this dynamic. There is a sense in labs of “it could happen to us too.” “The previous two UNOCs were important, but this one is more so with what’s happening in the U.S.,” says Gaill. “We see clearly that rationality isn’t obvious for everyone, and we scientists are the first to be attacked. It’s crazy.” Though developed before these events, the Congress will “respond” to this wave, promises Gaill, one of the architects of the 2022 One Ocean Summit. “It will be a way to affirm our values. Ursula von der Leyen [President of the European Commission] said at the Sorbonne that fundamental research is a European value, at the heart of the European spirit. That was the first time I heard this so clearly. For me, it’s very important.”

Tools to Facilitate Knowledge and Action

For the ocean and its climate driver, time is running out to stop degradation. But ocean governance is fragmented and sectoral. “We lack, as for climate (IPCC) or biodiversity (IPBES), a decision-support tool,” says Poivre d’Arvor.

During the Congress and UNOC, several major initiatives will launch to “sustainably feed public ocean action.” Oceanographer Jean-Pierre Gattuso, co-organizer, notes, “We see that when positive actions, effective programs, and restorations are implemented, ocean health can be restored.” Three initiatives stand out for their long-term potential, collaboration, operational philosophy, and holistic ambition.

Ipos: The International Platform for a Sustainable Ocean

Poivre d’Arvor calls it “UNOC3’s scientific legacy.” “Ipos’s mission is to strengthen states’ capacity to implement their commitments,” explains coordinator Maxime de Lisle. Conceived and led by biologist Françoise Gaill, it was first presented as an ocean IPCC—“that was the initial idea,” she confirms. “An overambitious ambition,” admits Poivre d’Arvor. It’s quite different now; its goal is to use knowledge to develop concrete policy options.

Its strength lies in a simple question-answer principle: a state requests to improve a specific objective; Ipos creates an interdisciplinary working group and delivers “a knowledge synthesis in weeks” or “policy proposals in a year.”

Ipos aims to cover all marine environment topics: plastic pollution, marine protected areas, overfishing… “It will be tailor-made,” boasts De Lisle, “fast, and will use artificial intelligence”—an energy-intensive technology—“and be inclusive”: academic, indigenous, private sector, and civil society knowledge will be mobilized. Case study results will be publicly shared.

A test is underway in the Seychelles. “We developed with them an AI tool, ‘OceanGPT,’ which helped them work on circular economy policies: how to prevent plastic pollution from reaching the sea and how to create blue economy in the country.” OceanGPT draws from 800,000 articles and reports.

From September, 10 to 20 countries will be supported for two years. By 2027, Ipos should be integrated into UNESCO. Alongside France, China is the main power supporting the platform. Funded largely by the European Commission, insurer Axa, luxury group Kering, and the Kresk 4 Ocean fund, it starts with a budget of just over 5 million euros.

Mercator Ocean Becomes Intergovernmental

Mercator Ocean is a European organization based in France monitoring ocean conditions (temperature, currents, rise, acidity, salinity, biomass, oxygen…) for over 20 years. It provides forecasts; for example, it powers the Copernicus Marine Service, the EU space program that collects and delivers Earth data, including the annual Ocean State Report. All sea users can use this service.

Mercator is transforming into an intergovernmental organization dedicated to digital ocean systems and services. “We invite all European states [plus Iceland, Norway, Monaco, and the UK] to join governance,” says Pierre Bahurel, Mercator’s director. This provides “a decision-support tool.”

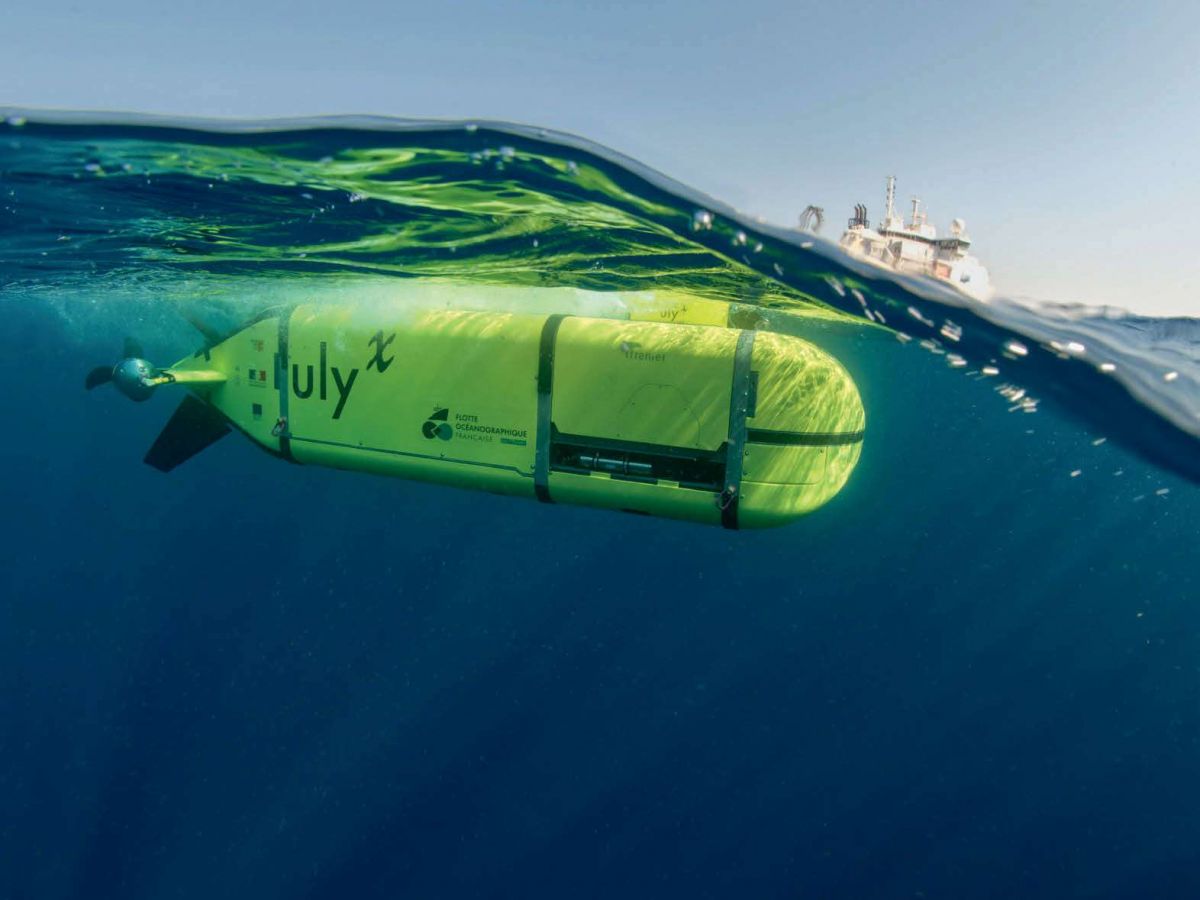

The scientific pillar of this pact is the Digital Twin of the Ocean (DTO), which Bahurel calls “a new era of operational oceanography.” Since the 2022 One Ocean Summit in Brest, a prototype will be unveiled. It will be a virtual, interactive ocean model compiling satellite and thousands of sensors’ data worldwide. These data cover all ocean behaviors and features, surface and depth, real-time and past observations, and will enable future scenarios, e.g., modeling plastic waste drift with currents. DTO aims to support the EU Ocean Pact, soon to be adopted as a unified policy framework.

Source: rfi