It was President Kaïs Saïed who first raised the issue. On September 30, 2025, during a meeting at the Carthage Palace with three members of the government — Mustapha Ferjani (Health), Habib Abid (Environment), and Fatma Thabet (Industry, Energy, and Mines) — the Head of State described the establishment of the chemical complex in Gabès as a “true crime” that led to the “assassination of the environment and public health” in the city.

From a legal standpoint, this falls under what is known as a crime of ecocide — a crime recognized internationally at the same level as human genocide and the large-scale use of chemical weapons during armed conflicts. One such example is the Vietnam War, during which the United States used napalm extensively, dropping around 352,000 tons of the incendiary substance between 1963 and 1973.

Ecocide refers to severe and long-lasting damage inflicted upon the environment through human activities such as pollution, biodiversity destruction, and climate change.

“The establishment of the Gabès chemical complex is a real crime. It has led to the assassination of the environment and public health throughout the region.”

If we apply this definition to the pollution in Gabès (a city of about 150,000 inhabitants), we can clearly observe an act of ecocide given the extent of the damage caused. A few examples stand out.

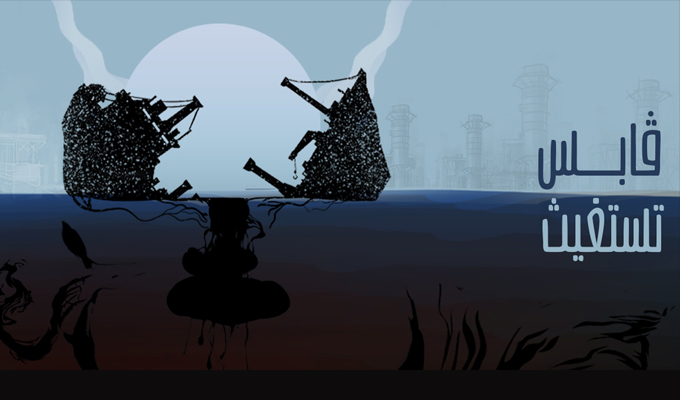

The first involves the annual discharge of nearly 10 million tons of phosphogypsum — an extremely polluting material — into the sea. This dumping has severely affected the ecosystem of the Gulf of Gabès, a body of water once known as one of the main spawning grounds of the Mediterranean and home to the basin’s only coastal oasis.

The second concerns the impact of pollution from Gabès’ chemical industries. The city’s 150,000 residents are directly exposed to this marine pollution, which also affects air quality as well as the soil and subsoil. According to experts, it is believed to be responsible for rising cases of cancer and chronic diseases such as asthma.

“Nearly ten million tons of phosphogypsum — a highly toxic substance — are discharged each year into the Gulf of Gabès, destroying a unique ecosystem.”

The third issue is the overexploitation of the region’s water resources. To meet their massive water demands, Gabès’ chemical industries have for decades drawn on groundwater originally intended for the oases and even tapped into the drinking water supply managed by SONEDE. The result: Gabès has become, through the combined effects of pollution and resource depletion, the most polluted city in the Mediterranean, and indeed the victim of an act of ecocide.

The crime of ecocide still lacks an international legal definition

This crime, which has yet to gain official international recognition, does not have a universally accepted legal definition. However, the term “ecocide” is used when environmental damage causes irreversible consequences, affecting ecosystems, animal and plant species, and/or the human communities that depend on them.

For this reason, the urgent legal complaint filed by Tunisian lawyers — particularly from the Gabès Bar — against the Tunisian Chemical Group (GCT), requesting the suspension of its polluting activities, has little chance of succeeding before national or international courts.

“Through the overexploitation of its resources and industrial pollution, Gabès has today become the most polluted city in the Mediterranean.”

As a result, this legal initiative is likely to remain primarily a symbolic gesture of solidarity, part of a growing citizen mobilization in Gabès in response to environmental degradation and its public health impacts. Demonstrations continue to demand the immediate shutdown of the industrial complex — a cry for justice that still struggles to be heard.