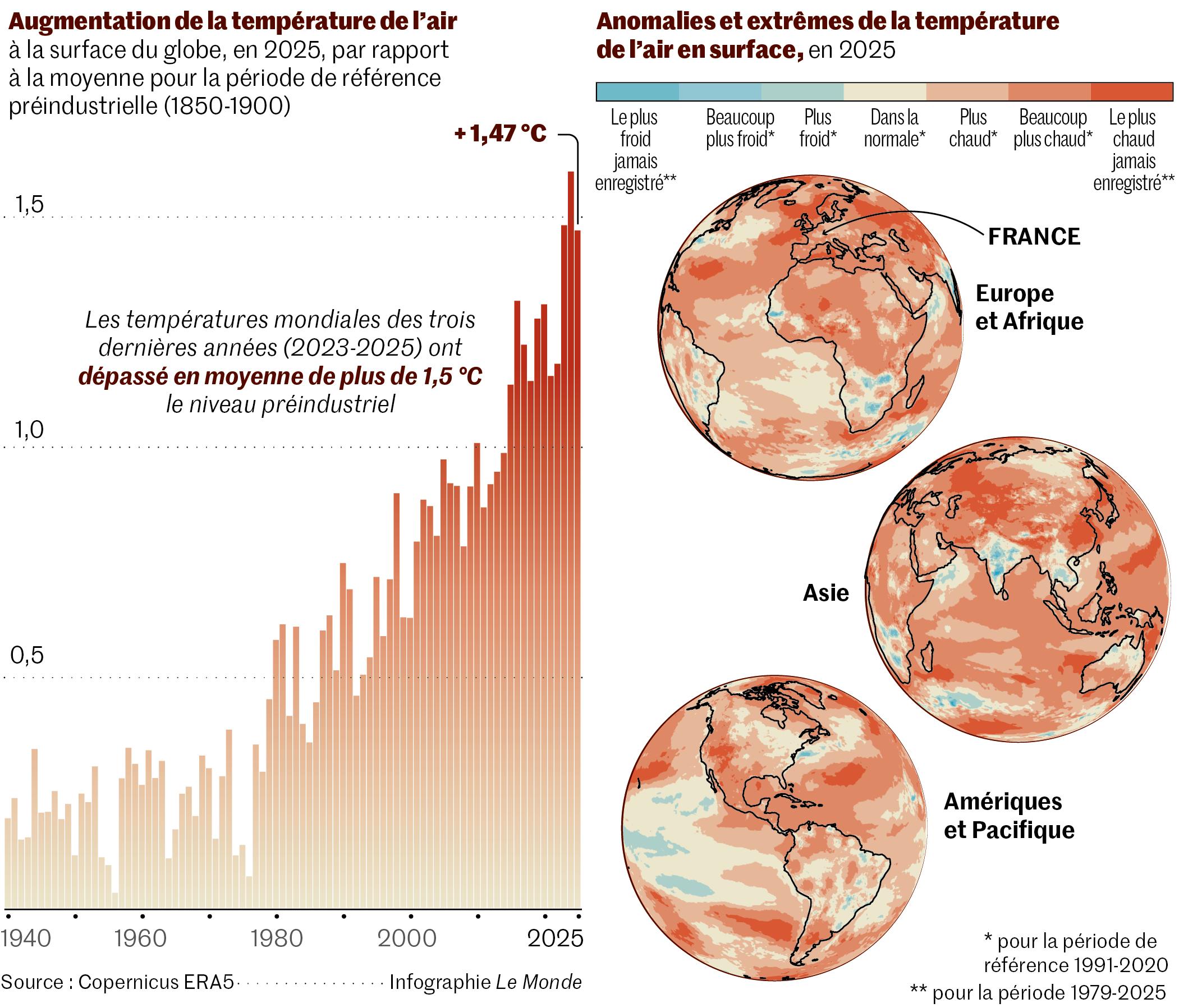

The planet showed no respite in 2025. After two already exceptional years, the heat did not subside: last year was the third warmest year ever recorded worldwide and in Europe, according to the European Climate Observatory Copernicus report published on Wednesday, 14 January. For the first time, a three-year period (2023, 2024, and 2025) exceeded the symbolic 1.5 °C warming threshold compared to the pre-industrial era, the most ambitious limit of the Paris Agreement. Three years, three red alerts, and a climate settling persistently into the exceptional.

In 2025, global surface air temperatures were 1.47 °C above pre-industrial levels (1850–1900). 2025 ranks just behind 2023 (−0.01 °C) and slightly cooler than 2024 (−0.13 °C), which remains the record year and the only one to surpass 1.5 °C. The past eleven years have all been the warmest ever recorded.

“The Paris Agreement is not violated,” says Samantha Burgess, strategic climate officer at the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (part of Copernicus). The treaty’s target is meant to be assessed over longer periods than one or three years. Nevertheless, at the current pace, the 1.5 °C limit is expected to be permanently exceeded by 2030, a decade earlier than scientists projected in 2015.

These past three “exceptionally hot” years are not anomalies: they reflect record accumulation of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, primarily due to human emissions from coal, oil, and gas combustion, compounded by reduced CO₂ absorption by natural sinks such as forests, which are in poor condition.

Polar Regions Particularly Affected

Natural factors also contributed: the El Niño phenomenon warmed the oceans in 2023 and 2024. Despite the arrival of the reverse La Niña event, 2025 remained extremely warm. Reduced aerosols (which have a cooling effect) and fewer low clouds also contributed. But uncertainties remain. “It is too early to determine whether we are entering a permanent acceleration of global warming or whether this is natural climate variability,” says Burgess.

The poles, key indicators of global climate stability, were especially impacted. Antarctica recorded its warmest year ever, and the Arctic its second warmest, exacerbating ice melt and marine ecosystem disruption. In February 2025, the combined polar ice extent reached its lowest level since satellite observations began in the late 1970s. Norway, the North Sea, the Northeast Atlantic, and Central Asia also experienced record heat.

Over half the globe saw numerous “high thermal stress” days, with felt temperatures of 32 °C or higher, challenging organisms.

Ocean Heat Records

The oceans absorbed record amounts of heat, according to a study published on 9 January in Advances in Atmospheric Sciences. In 2025, the upper 2,000 meters of the oceans absorbed 23 zettajoules more than in 2024—equivalent to 200 times the world’s 2024 electricity production. Greenhouse gases primarily warm the oceans, which store 90 % of the excess energy from climate change, driving sea level rise, extreme storms, and coral die-off.

Extreme Weather Events

Rising temperatures are not abstract numbers: they translate into more frequent and severe extreme events. Monsoons in Pakistan, wildfires in California, floods in Indonesia and Texas, heatwaves and fires in Europe, and Hurricane Melissa in the Caribbean affected all regions, causing casualties, infrastructure damage, and economic losses. Climate disasters resulted in $224 billion (192.2 billion €) in global economic losses in 2025, according to Munich Re, down nearly 40 % from 2024 due to the absence of U.S. hurricanes for the first time in ten years. However, the situation remains “alarming,” with 17,200 deaths. Extreme events continue in early 2026, with fires in Australia and Argentina’s Patagonia.

Outlook for 2026

“2026 will likely rank among the top five warmest years,” notes Burgess. Ocean temperatures have slightly decreased so far, but a potential El Niño later in the year could trigger another heat spike. Uncertainties will remain high until spring. “The question is not whether a new El Niño, and thus a new temperature peak, will occur, but when,” emphasizes Carlo Buontempo, director of the European Copernicus Climate Change Service.

Environmental Setbacks

Scientists emphasize that every fraction of a degree matters. Yet progress on greenhouse gas reduction has slowed, hindered by climate skepticism and environmental rollbacks in the U.S. and Europe—despite rapid global growth in renewables, driven by China.

In North America, emissions in the world’s largest economy and second-largest polluter rose by 2.4 % in 2025, driven by a cold winter and increased data center consumption, even before Donald Trump’s fossil fuel–friendly policies took effect. In Europe, countries like France and Germany continue to reduce emissions, but at a slower pace than previous years.