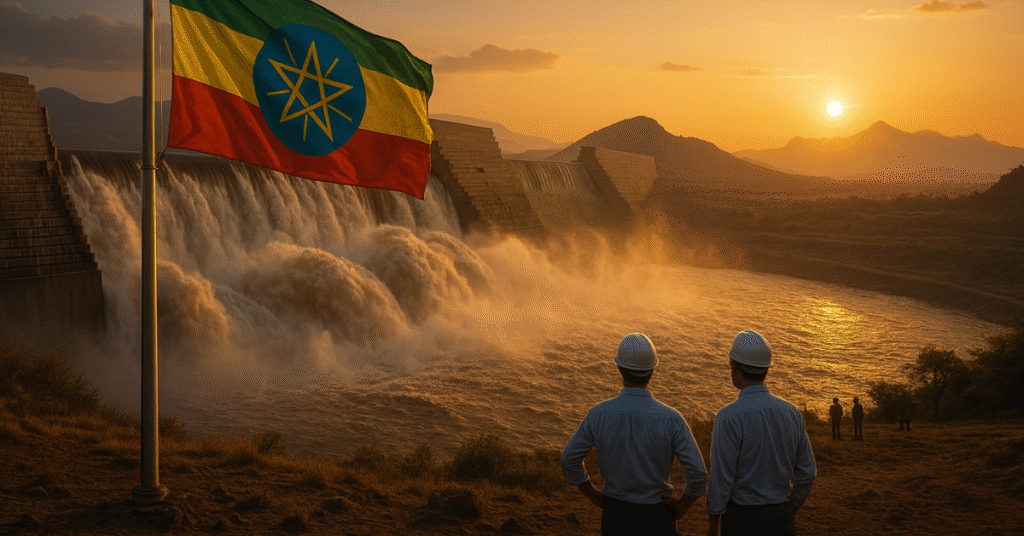

Addis Ababa, July 2025. The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD), this giant concrete structure erected on the Blue Nile, has just completed its final filling. For Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, it is a victory: Ethiopia is making history as Africa’s hydroelectric power giant. For Egypt, it is a strategic slap in the face, an existential threat.

Behind the technical feat lies an old civilizational dispute resurfacing. The Nile, a sacred river for some and a vital artery for others, has become a battleground again. Cairo, firmly clinging to its historic rights inherited from colonial treaties, refuses any concession. Sudan fears a possible reduction in its water flow. And while diplomatic offices hustle, Ethiopian turbines are already turning.

The return of the river powers

In Africa and beyond, water has become a geopolitical weapon. The GERD is more than a dam: it is a lever of influence, a civilizational project, a revenge against an order imposed from London or Paris. Addis Ababa intends to break free from energy fatalism and emancipate itself from a model of dependence.

But wielding this hydraulic weapon carries a diplomatic price. By refusing to share management of the Nile’s flow, Ethiopia has alienated Cairo and Khartoum. Tripartite negotiations are stalled. Each cycle replays the same dance: official smiles, technical deadlocks, veiled threats.

No bombs have exploded yet in this conflict, but fault lines are very much active. Egypt invests in armed drones, deploys aggressive diplomacy at the African Union, and forges backdoor alliances with Eritrea. Water has become a hostage to politics.

Addis Ababa seeks the sea

Another great dream of Abiy Ahmed is access to the sea. Since Eritrea’s secession in 1993, Ethiopia has been landlocked, which for a country of over 120 million people is a strategic aberration.

Addis Ababa has never accepted this landlocking. So it maneuvers. It signs discreet agreements with Somaliland — a non-recognized state willing to cede a port in exchange for diplomatic recognition. It threatens Djibouti by increasing dependence on land corridors. It challenges Eritrea over still disputed borders.

In January 2024, in a bold and risky move, Ethiopia signed a memorandum of understanding with Somaliland, this self-declared but internationally unrecognized republic, to gain access to the Red Sea. In return, Addis Ababa plans to officially recognize Somaliland as a sovereign state — a first on the African continent since South Sudan’s independence. A diplomatic shockwave.

Addis Ababa’s motivation is clear: to end its landlock. Since 1993, deprived of its coastline by Eritrea’s secession, Ethiopia has been almost entirely dependent on the port of Djibouti for foreign trade. This dependence is seen as a strategic humiliation by its military and political elites. By allying with Hargeisa, Somaliland’s capital, Abiy Ahmed aims to break this vulnerability.

But this frontal move disrupts regional balances. Somalia, which regards Somaliland as a dissident region, sees it as a direct sovereignty breach. Mogadishu threatens to cut ties with Addis Ababa. The African Union, embarrassed, struggles to arbitrate between the colonial-era inviolability of borders and the realities on the ground.

And in the shadows of this maneuver, another power advances: Turkey…

Ankara’s long arm in the Red Sea

Turkey no longer hides its ambitions in East Africa. Present militarily in Mogadishu since 2017, where it maintains a military base and a training center for the Somali army, Ankara views the rapprochement between Addis Ababa and Somaliland very warily. Ethiopia’s project weakens Somalia, Turkey’s privileged partner in the Horn of Africa.

Ankara positions itself as defender of Somali unity — a stance both strategic and symbolic. It fears that recognizing Somaliland will open the Pandora’s box of separatisms in Africa while weakening its own military influence in the region. Turkey, an ally of Qatar and rival of the Emirates in the Horn, plays a delicate balancing act, supporting Mogadishu’s institutions while preventing broader destabilization.

But Ankara does not only act behind the scenes: it invests, builds, equips. Its companies are active in ports, hospitals, and roads from Djibouti to Mogadishu. Through the Horn of Africa, Turkey deploys a discreet neo-Ottomanism mixing humanitarian aid, religious diplomacy, and military presence.

This maritime quest has become an obsession for Ethiopia. For trade, arms, exporting electricity or agricultural products, Ethiopia needs an outlet to the Red Sea. Without it, it remains a giant dependent on logistics, vulnerable to every regional crisis.

The elusive peace

But while Addis Ababa looks outward, internal fires smolder. After the Tigray War (2020–2022), ended by a fragile Pretoria agreement, new tension hotspots have flared: Amhara, Oromia, Benishangul. The ethnic federalism established in the 1990s continues to fuel mistrust towards the center.

Far from uniting, Abiy’s reform has fractured. The federal army is exhausted by successive combats. Regional special forces, dismantled in the name of unity, have often joined autonomous militias. The 2026 general elections are approaching amid a toxic atmosphere. The specter of a new civil war is not excluded.

A coveted power under scrutiny

Ethiopia is an enigma. A historic power — never colonized, a millennial empire — it is also a laboratory of African chaos. On its soil, China builds, Turkey arms, Russia recruits, and the US watches.

Host country of the African Union, BRICS member, hub of pan-Africanism, Addis Ababa fascinates as much as it worries. It could become a pillar of stability. It could just as well become the epicenter of regional collapse.

Ethiopia, or the imperial vertigo

One must understand one essential thing: Ethiopia dreams of an imperial destiny in a fragmented world. It wants greatness without having solved its own unity. It aspires to modernity but clashes with tribal loyalties. It seeks strategic autonomy but depends on corridors, dams, and shifting alliances.

It is an unstable giant shaking the entire Horn of Africa. If Ethiopia falters, Djibouti trembles, Mogadishu collapses, Khartoum tightens, Cairo panics. If it succeeds, it becomes the engine of East Africa. If it fails, it ushers in an era of disorder.

The Nile as a theater of a multipolar world

The GERD affair is much more than a local conflict. It is a test for international law, a revelation of new multipolar rivalries, a metaphor for 21st-century Africa.

Ethiopia walks a tightrope. Its future is poised between two waters: the Nile, a source of discord, and the Red Sea, a gateway to salvation.

As often in geopolitics, intentions and promises count less than the subtle balance between power, legitimacy, and stability. Today, Addis Ababa has power, little national legitimacy, and stability still hanging by a thread.

Source: lediplomate