In 2019, Jeanne Socrates achieved the feat of sailing solo around the world without stopovers or assistance. Today, she continues her journey, cultivating her joy and passion for wildlife.

As the setting for our meeting with Jeanne Socrates, we dreamed of the ocean: swirling foam, fleeting sharks, stars reflecting infinitely on the black waves, drowned in the glow of fluorescent plankton. At the very least, we would have settled for a port, rocked by the cry of seagulls and the clinking of ropes against the masts. But here’s the thing: on the day of our exchange, the navigator is in Whangarei, New Zealand, preparing to set sail for the Polynesian archipelago of Tonga. To join her, there are two options: 48 hours of round-trip flights—and 11 tons of CO2 in the atmosphere—or months of sailing. Back to reality. We will settle for a video call, at the only time of day when the ten-hour time difference allows us to connect: at our place, the sun is rising; on her side of the Pacific, night is beginning.

The English adventurer, who will celebrate her 82nd birthday in August, has been sailing for over thirty years on all the seas of the globe. In 2019, at the age of 77, she managed to complete a 320-day solo, unassisted, non-stop circumnavigation. No sailor had previously achieved this feat at such an advanced age. Jeanne Socrates was not new to this. A previous voyage, six years earlier, had already made her the oldest female circumnavigator in history.

She appears on the screen from a low-angle shot, with a big mischievous smile anchored on her face. A silver mane frames her lively eyes, bordered with crow’s feet. The image is pixelated. Nevertheless, behind her, we can distinguish the contours of the 11-meter vessel with which she braved the southern seas, their icy storms, and their monstrous waves: a wooden partition, portholes covered with blue canvas, a few tools scattered on the chart table. “My boat is my other half. My pair, my companion, my friend, my helper,” she comments in her tender voice, constantly interrupted by bursts of laughter.

Navigator Jeanne Socrates and her loyal smile, here in 2012. Jeanne Socrates

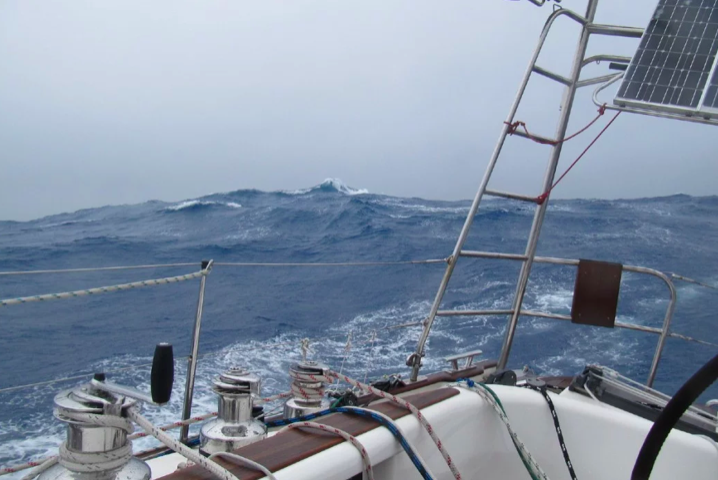

Like many wealthy seniors, this mother of two grown children might have dreamed of spending her golden years on a cruise liner. Instead of the luxury of these ships with their spas, jacuzzis and restaurants, she preferred the discomfort of sailing ships and their string of galleys. During her last passage around Cape Horn – the “Everest of sailors”, located at the southern tip of Latin America – in 2019, her main sail tore. She had to sew it back on by herself, perched on her mast, tossed about for hours by a ferocious swell. On several occasions, insane winds almost turned her boat upside down. One day, in the Southern Ocean, they were so violent that she found herself “soaked from head to toe”: “I had a hole in my cabin,” she recounts, her tone still full of anguish.

But nothing could stop Jeanne Socrates from staying afloat, valiant and determined. Over the years, she has learned to repair everything on board. It comes slowly, as things break,” she smiles. As long as you’ve got a sail, an anchor and a rudder, know where you’re going and keep your wits about you, you can sail. The rest is a bonus.

One of the incredible sunsets she witnessed on her sailboat, here in Punta Mita, Mexico. Jeanne Socrates

Leaving the ocean and becoming a landlubber again: that would be the real mission impossible for her. We asked her why she was so keen to stay at sea, despite age and difficulties. “I love everything to do with sailing,” she sums up simply. Living with the wind and the tides, with no one around for thousands of kilometers; watching the full moon reflected in the water; greeting, in the early morning, the dolphins playing on the side of the ship; drinking a coffee facing the horizon; the company of albatrosses… “They come right alongside the boat and they’re so happy to be there. They come right alongside the boat and look you in the eye. It’s wonderful.”

Off the coast of South Africa, a whale once ventured right next to her ship while she was cooking a butternut squash; during a crossing of the equator, another appeared in front of her, projecting a cloud of hot air into the atmosphere. “It was spectacular!”

“At the age of 12, I taught myself to dive”.

Nothing predestined Jeanne Socrates for this existence. The sailor was born in 1942, at the height of the Second World War, to a teenage mother and an Australian aviator father whom she never met. From the age of 5 to 9, she lived in an orphanage in East London. No one around her was sailing. But her love of water and the wild was already in the bud.

« I’ve always loved swimming. When I was 12, I taught myself to dive in the school pool,” she recounts. To get to class, she had to cross a large park. “When I realized there were birds there, I started hiding in the bushes to try and see them. Then I’d try to identify them by looking in the books.”

As an adult, Jeanne Socrates became a math teacher. She wasn’t introduced to sailing until she was 48, by chance, during a school trip with her pupils to the Isle of Wight in southern England. The virus took hold. Her passion for the wind never left her.

Jeanne Socrates : «J’ai appris, j’ai pris confiance en moi, et soudainement, un jour, j’ai réalisé que je gérais.» © Jeanne Socrates

For years, she and her husband Georges had been taking one training course after another. Their goal was to spend their retirement on the water, exploring the world. Their dream was partly realized when, in 1997, they bought their first boat, Nereida – named after the Nereids, the sea nymphs who, in Greek mythology, served the god Poseidon. The Canaries, Nova Scotia, Bermuda, Cuba, Puerto Rico… Together, they enjoyed four great years of adventure. But in September 2001, Georges began to suffer from back pain. He succumbed to cancer in March 2003. “He couldn’t enjoy the boat for long,” Jeanne Socrates murmurs.

Modest silence. She continues: “After that, what could I do? I didn’t want to leave the boat, I loved it too much. And you make a lot of friends on a sailboat. You always meet people who are welcoming and ready to help.” At the age of 61, the young widow decided to attempt her first solo sail from the island of Bonaire, north of Venezuela, to Fort Lauderdale, Florida. “And then I just kept going. As time went by, the small steps became bigger and bigger. I learned, I gained confidence, and suddenly, one day, I realized I was managing.”

“Why should I stop? The plan is to keep sailing wherever I please.” Jeanne Socrates

Age, “it’s just a number”.

First round-the-world attempt in 2007. Bad luck: 60 miles (96 kilometers) from the finish, on a windless night, an autopilot failure threw the Nereida off course while Jeanne Socrates slept. The boat ran aground on a beach north of the Mexican town of Acapulco. The sailor woke up to water and sand all over her cabin. “It was horrible,” she recalls. All she was able to salvage from her floating “teammate” were a few instruments, miraculously saved thanks to the help of locals.

The shock didn’t stop her momentum. “I sold my house, and thanks to the boat’s insurance, I was able to buy a second one, Nereida II. She’s her big sister,” she smiles. Jeanne Socrates has been living aboard her for fifteen years, and hopes to stay “as long as possible”. “Why should I stop? The plan is to continue sailing wherever I please.

During a turbulent voyage in the Southern Ocean. Jeanne Socrates

Jeanne Socrates is blessed with good health. She maintains it by doing a few squats and sit-ups whenever she can think of them. Sometimes she forces herself to run on deck, “just for a bit of exercise”. Of course, she confesses, time has made her less prompt. “It’s not a problem. You just have to take your time.” Age, she believes, “is just a number: it’s the mental attitude that counts”.

Hers is no different from that of a young girl. The years have not eroded her curiosity, sociability or sense of wonder. During a stopover in Sweden, the sailor learned the basics of the Germanic language; her stopovers in Mexico have made her a Spanish buff, which she practises by chatting, via her VHF radio, with the Chilean, Ecuadorian and Argentinean sailors she meets on the high seas.

I always find a reason to party,” she sparkles. The passage of a cape, a meridian, the equator… It’s important to celebrate things.” Songs by Abba and English jazzman Acker Bilk often rock the ship’s hull. “I’ve got a dancefloor here – it’s small, but I can dance. And I’ve got a pole to hang on to!” She laughs. “I love life!” The exchange comes to an end. The next day, she has to get up early to pick up some metal parts in town. After final repairs, Nereida II and her skipper should be ready for the Pacific. Their epic journey seems far from over.

Source: Reporterre