Abstract

Climate-induced distribution shifts are particularly challenging for fisheries targeting fish populations shared between Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) and the high seas, known as straddling stocks. Here, we combine multiple datasets and ecosystem modeling to identify the presence of straddling stocks worldwide and examine the management implications of climate-driven changes. We identify 347 straddling stocks across 67 species, including highly migratory and less mobile species. Our results suggest that, regardless of the climate scenario, at least 37% and 54% of stocks are projected to shift between EEZs and the high seas by 2030 and 2050, respectively. More stocks are expected to move towards the high seas, and large migratory stocks will shift between Regional Fisheries Management Organizations (RFMOs). Coastal states and RFMOs must revise governance frameworks to support sustainable and equitable adaptation to changing stocks. Developing such strategies requires cooperation among management bodies within EEZs and the high seas.

INTRODUCTION

The biogeography of marine species is determined by historical and contemporary factors such as their evolutionary history and biology, surrounding environmental conditions, and anthropogenic factors like exploitation. In particular, the distribution of marine ectotherms such as fish and invertebrates is strongly influenced by oceanic conditions including temperature, oxygen, salinity, and net primary production (1). While fisheries management and governance are linked to human-defined geographical boundaries, marine species are not. Their complex movements and habitat use may span the Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) of multiple countries and waters beyond national jurisdictions (hereafter “the high seas”). Thus, many exploited fish and invertebrate “stocks” are shared across politically defined but ecologically contiguous ocean areas.

Shared stocks can be classified into four non-exclusive categories: (i) transboundary — stocks shared between neighboring EEZs, (ii) straddling — stocks shared between neighboring EEZs and the high seas, (iii) overlapping — stocks spanning multiple EEZs and the high seas, and (iv) discrete high seas — stocks limited to the high seas (2). Shared stocks are often managed by Regional Fisheries Management Organizations (RFMOs). Among the 18 RFMOs operating globally, five manage exclusively highly migratory species (mainly tunas): the Commission for the Conservation of Southern Bluefin Tuna (CCSBT), the Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission (IATTC), the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT), the Indian Ocean Tuna Commission (IOTC), and the Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission (WCPFC). All these RFMOs have defined areas covering multiple species, except CCSBT which manages a single tuna species without a specific convention area. The remaining 13 RFMOs manage other straddling and discrete high seas fish stocks, such as salmon and flatfish (3). Previous studies identified thousands of transboundary stocks (4,5) with total catches estimated at 48 million tonnes and valued at 77 billion USD in 2014 (4), while catches of highly migratory species (the most commercially important tuna species) were valued at 11.7 billion USD in 2018 (6).

Managing shared stocks is more challenging than species confined to a single EEZ. It depends on correctly identifying distribution boundaries, the importance of stocks to resource users, and cooperation among users and managers (7–9). Fish stocks are more likely to be overexploited when shared than when confined to one EEZ (10–12). One key challenge in identifying shared stocks and estimating their importance for fisheries is that stock distribution boundaries are often unclear, complicating the determination of the nature of sharing [e.g., overlapping or transboundary (13)]. Accurately delineating fish stocks requires a strong understanding of species biogeography and consensus on assessments among the countries whose waters are inhabited by the stocks (7,8).

Climate change adds another layer of complexity to studying, governing, and managing straddling stocks (14). Climate change causes shifts in marine species distributions, with many moving towards higher latitudes, deeper waters, or along local environmental gradients such as localized currents and upwelling systems (15). These distribution shifts alter the sharing of fish stocks across jurisdictional and management boundaries (16). Recent research has highlighted the consequences of these changes for managing transboundary stocks (14,17), including the potential emergence of new transboundary stocks (18) and the departure of some stocks from EEZs (19). However, the extent of distribution changes of straddling stocks has not been quantitatively determined (i.e., including the high seas), limiting effective governance of shared stocks under different climate change scenarios (20).

This study explores the impact of climate change on the global distribution of straddling fish stocks. Specifically, we aim to identify stocks overlapping the high seas and EEZs and study the effects of climate-induced distribution changes on the proportion of straddling stocks between EEZs and the high seas. We hypothesize that (i) straddling stocks consist mainly of large pelagic species, and (ii) their relative share between the high seas and EEZs will change in the 21st century due to climate change. First, we identify straddling fish stocks worldwide and project their distributions using a mechanistic population dynamics model driven by outputs from three Earth system models (ESMs) under two climate change scenarios [low emissions: Shared Socioeconomic Pathway 1 – Representative Concentration Pathway 2.6 (SSP1-2.6), and high emissions: Shared Socioeconomic Pathway 5 – Representative Concentration Pathway 8.5 (SSP5-8.5)]. Then, we examine potential climate-driven changes in straddling stocks between EEZs and the high seas and discuss management and governance challenges for internationally shared fish stocks, highlighting the need for dynamic international strategies. Additionally, we examine shifts in straddling stocks of highly migratory species within tuna RFMOs. This study contributes to the growing literature seeking to better understand marine species shifts in an era of rapid environmental change, focusing on climate-driven habitat changes of economically important straddling stocks and the implications for international fisheries management and governance.

RESULTS

Identification of straddling stocks

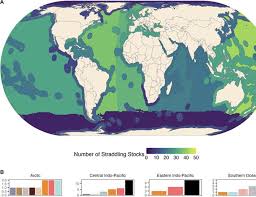

Our modeling results suggest that 67 commercially exploited straddling species [including 15 highly migratory species as defined by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS)] comprise at least 347 straddling fish and invertebrate stocks worldwide (Table S1). The majority (57%) are large pelagic species. The EEZs of temperate Australasia, central Indo-Pacific, and temperate North Atlantic harbor the highest numbers of straddling stocks (Fig. 1A). Highly migratory species such as tunas and marlins constitute the most widely shared commercial group across all regions. Among the 10 most shared species are silky shark (Carcharhinus falciformis), blue shark (Prionace glauca), wahoo (Acanthocybium solandri), skipjack tuna (Katsuwonus pelamis), and yellowfin tuna (Thunnus albacares). EEZs in temperate South America are the only ones not dominated by highly migratory straddling stocks. Instead, they are characterized by relatively less mobile perch-like species such as Chilean jack mackerel (Trachurus murphyi), spanning the EEZs of Chile and Peru, and Patagonian toothfish (Dissostichus eleginoides), covering the EEZs of Argentina, Uruguay, and the Falkland Islands (Malvinas). These species are among the region’s most widespread fish stocks.