Since Abiy Ahmed came to power in April 2018, Ethiopia has adopted an offensive strategy to strengthen its position in the region. This strategy aims to establish military, economic and energy domination. From the bilateral agreement with Somaliland to the unilateral decision to fill the GERD dam, in defiance of ongoing negotiations, nothing seems to stop Addis Ababa’s expansionist policy. Nostalgic for the prosperous reign of Menelik II, the Ethiopians want to restore its “imperial grandeur” to Ethiopia.

Denunciation of historic agreements

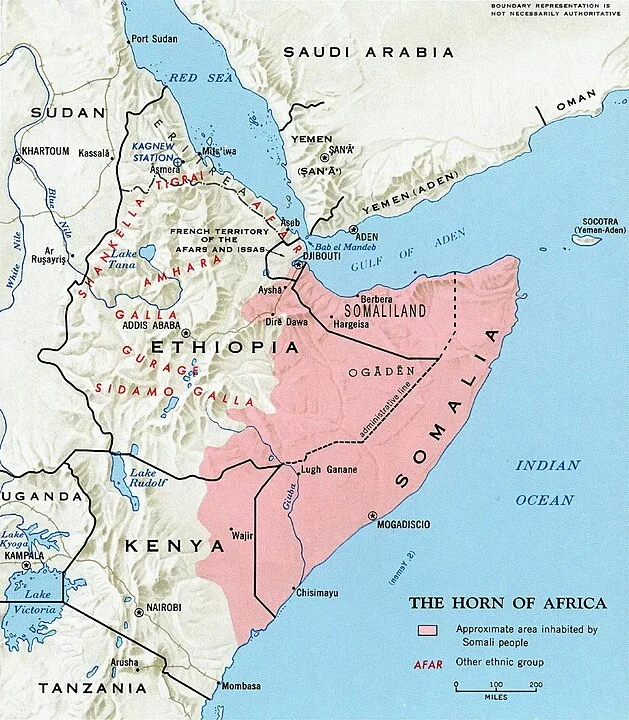

Since Eritrea’s independence in 1993, Ethiopia has faced the reality of having lost direct access to the Red Sea. This situation has led to a significant dependence on the port of Djibouti for its international trade (95% of exports and 80% of imports). With annual port fees amounting to approximately $1.5 billion, this dependence has led to considerable economic repercussions, largely contributing to a strain on national finances. Despite past discussions about the possibility of using the Eritrean port of Assab, no viable agreement has been reached, even after the two countries joined forces during the Tigray War. Additionally, hopes of accessing the Berbera port in Somaliland evaporated in 2022 when Ethiopia lost its rights due to its inability to financially participate in the project.

This series of setbacks has prompted Ethiopia to question historic agreements that have contributed to its regional economic dependence. Thus, Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed has expressed his desire to end Ethiopia’s enclave by calling the country’s landlocked borders a « geographic prison. » He called for negotiating port access with Eritrea, Djibouti and Somalia, threatening to use force if necessary. Furthermore, on November 16, Sahle-Work Zewde, President of the Federal Republic of Ethiopia, proposed avenues for reflection during the African Economic Conference in Addis Ababa. She highlighted the importance of “import substitution and export-oriented industrialization” for sustainable industrial development on the African continent. These declarations illustrate this dual desire to end dependence on Djibouti and to obtain access to the sea in order to export massively.

Map of the Horn of Africa

At the same time, the Ethiopia-initiated Nile Dam project, known as the Grand Renaissance Dam (GERD), is causing a major regional crisis. Ethiopia, seeking to diversify its water resources, launched this colossal project to increase its electricity production (5,150 MW targeted) in order to export it. The announcement in 2011 by the Ethiopian government of the construction of the dam on the Abbey River, a project historically desired by Ethiopians, is hailed as an act of national pride and unity. Driven by popular will, the financing of the project is ensured by massive contributions from the population and the Ethiopian diaspora, civil servants having been called upon to contribute by paying one month of their salaries. Despite technical and political challenges, the GERD represents hope for Ethiopia’s energy and economic future.

However, Egypt and Sudan see the project as a threat to their water supplies, citing historic agreements that gave them privileged rights to the Nile waters. These agreements, concluded during the 20th century, were based on colonial treaties granting Egypt and Sudan full control of the Nile’s water resources. The construction of the GERD marks a turning point in regional dynamics, shaking Egypt’s hegemony over the Nile. The agreement signed by Ethiopia with other countries bordering the river shifts the political center of gravity from the Nile upstream, causing increasing tensions between Ethiopia, Egypt and Sudan. The Cairo government is concerned about the impact on its water supply and agriculture. Indeed, filling the dam in 3 to 5 years, as recommended by Ethiopia, could lead to an annual reduction of 67% of the country’s arable land. Despite political tensions and stalled negotiations for a binding agreement, Egyptian farmers are adopting crops that consume less water, illustrating a local desire to adapt to anticipated changes. This adaptation, contrasting with political alarmism, underlines a local desire to find solutions to political uncertainty.

Sudan takes an ambivalent position. On the one hand, he fears Ethiopia’s control over the Nile, which could cause flooding and harm its own hydroelectric infrastructure. On the other hand, he sees in the GERD an opportunity to access cheap energy and better control the flow of the Nile, which could promote his agricultural production. At the same time, a territorial conflict around the Al-Fashaga triangle, reconquered in 2021 by Sudan, could also influence the negotiations on the dam, because it represents a lever of pressure against Ethiopia.

Negotiations of strategic partnerships and opportunistic alliances

Faced with these challenges, Ethiopia has adopted an offensive strategy by seeking to establish new partnerships and signing opportunistic alliances. The memorandum of understanding signed with Somaliland in January 2024 illustrates this new approach. This Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) provides for Ethiopian access to twenty square kilometers of coastline on the Gulf of Aden for a period of 50 years, in exchange for active lobbying for recognition of the independence of Somaliland by Ethiopia. and an entry of Somaliland into the capital of the airline Ethiopian Airlines. As a result, Ethiopia plans to establish a permanent naval base and develop commercial maritime services in the region. This naval base should also allow the development of an operational navy in the Gulf of Aden, essential for the credibility of the Ethiopian offensive strategy in the region. Since the signing of the MoU, Somalia has increased condemnations and calls for support from the international community. The diplomatic tension has still not subsided, as evidenced by this skirmish at the summit of the African Union.

Additionally, Ethiopia seeks to exploit geopolitical rivalries between China and the United States in the region to secure its national interests. Ethiopia and China recently announced the elevation of their bilateral relations to an “all-weather” strategic partnership. China is a key player in the region, with its naval base in Djibouti and its stated desire to make Ethiopia a bridgehead for its new Silk Roads in East Africa. Despite a late declaration of support for Mogadishu, which only had the effect of a formal reaffirmation of the indivisibility of the People’s Republic of China – particularly with regard to the question of Taiwan – on the part of Somalia and then of Ethiopia, China did not insist on denouncing the agreement. In addition to the significant fact that Somaliland is an ally of Taiwan, it is its partnership with Ethiopia that pushes China to be cautious. One of the important aspects of the latter is the import of electric cars. Indeed, the Ethiopian government recently decided to ban imports of cars running on fuel for private use, in order to encourage the purchase of electric cars produced in China. It is also in this logic that Ethiopia has continued at all costs to fill the GERD, designed to double electricity production and reduce the country’s dependence on oil.

The United States also expressed reservations about the memorandum of understanding signed with Somaliland, arguing that it « threatens to derail the fight that Somalis, Africans and regional international partners, including us, are waging against Al -Shabaab,” according to John Kirby, White House spokesman. However, supporting Ethiopia in this approach, which includes the development of a navy, would allow the United States to find a second strong ally (after Kenya) in Africa for securing the Red Sea. As a result of this crisis, the Horn of Africa is returning to the heart of the struggle for influence between China and the United States on the continent.

Normalization of relations with international bodies

Indeed, if Ethiopia implements a fait accompli policy with its neighbors, it is trying to normalize its relations with international institutions. The non-renewal of the UN Commission of Inquiry into the atrocities committed in Ethiopia, announced on October 4, 2023, illustrates this approach. Very critical of the Ethiopian government during the war in Tigray, Brussels now wants to turn the page and finish normalizing its relations with Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed. A line imposed by the Franco-German couple which is trying to compete with China in the region.

What prospects?

Despite international condemnation of the two ongoing crises, Ethiopia benefits from the strong support of China as well as less obvious allies who would find an interest in the development of its navy. A direct confrontation seems unlikely between the parties, neither having any real interest in an escalation of tensions. After the political crisis, Egypt is plunged into a serious economic crisis and its Sudanese neighbor is in the grip of a violent civil war. Ethiopia and Somalia, despite the diplomatic tension, maintain their diplomatic relations and Addis Ababa – Mogadishu flights are still operated regularly. The Ethiopians also have a means of putting pressure on their neighbor with the AU peacekeeping mission in Somalia (ATMIS) in which Ethiopian troops are incorporated. The weakening of the said mission, before its withdrawal in December, could cause a security vacuum that Somalia fears. This is why the Somalis are covering their backs with the recent signing of a military naval agreement with Turkey and a memorandum on the construction of five military bases with the United States. For its part, Ethiopia, already facing significant internal challenges such as the looming famine in Tigray and unrest in the Amhara and Oromo regions, as well as the potential threat of intervention by the Sudanese Rapid Support Forces on its borders, does not have the necessary resources to open a new front.

However, the uncertainty comes from Somaliland. The presidential elections in November could have significant repercussions in the region. The current political crisis, with contested elections and internal unrest, is weakening Somaliland’s president and raising concerns about regional stability. Although the situation is relatively stable compared to Somalia, some Somali generals warn of Ethiopia’s expansionist ambitions, raising the possibility of armed resistance. The question of a possible cession of territory in the Somaliland region is delicate, because it risks exacerbating nationalist tensions.

Ethiopia therefore has every interest in maintaining pressure on its neighbors while consolidating its strategic partnerships in order to avoid regional conflagration. The withdrawal of the peacekeeping mission in Somalia could lead to a new regional understanding to confront the terrorist threat. Recent tensions in the Red Sea, following attacks by Houthi rebels, could push the powers of the region to let Ethiopia develop its navy in order to play a role in securing the area. Ethiopia’s entry into the BRICS+ group in January 2024 will open up new markets for the country and may lead the group’s powers to intervene as mediators. The threat of a water war nevertheless risks hanging over the region for a long time if diplomatic solutions are not found.

The Ethiopian Institute of Foreign Affairs recently published a book titled « The Grand Strategy of Two Waters » exploring Ethiopia’s strategies regarding the Nile River and the Red Sea, highlighting issues of national security and maritime access . The strategic proposals aim to strengthen regional cooperation and encourage development, thereby providing an optimistic vision for the Horn of Africa in moving beyond the cycle of conflict to embrace progress and connectivity.