Unlike human intelligence, governed by a decision-making center (the brain), that of the marine world is organized without a conductor. It is based on a multitude of interactions where each physical process contributes to a global functioning. What to think of this analogy? Can we still talk about intelligence? Studying these forms of non-human organization invites us to rethink our definition of intelligence.

[An article from The Conversation written by Céline Barrier – Researcher, University of Corsica Pascal-Paoli]

PhD in marine sciences, specializing in the modeling of ecological processes, I work mainly on larval dispersion and connectivity between marine habitats, especially in coastal ecosystems of the Mediterranean.

My research consists in particular of « following sea larvae », in order to understand how information circulates in a complex natural system, through space, time and strong physical constraints. Marine « propagula« , larvae of fish or invertebrates, are not only living matter transported passively by currents.

They are also vectors of ecological information. Indeed, they carry a genetic heritage, traits of life history, an evolutionary memory and above all a fundamental potential: that of allowing, or not, the maintenance of a population in a given habitat.

Their evolution in space is an interesting example of how marine ecosystems are organized. This organization involves a very different form of intelligence from the one we know as humans.

An intelligence without a conductor

Marine ecosystems can be described as distributed systems: there is no decision-making center or centralized control.

The global organization emerges from the continuous interaction between physical (current, water column stratification), biological (larval development, mortality, sometimes behavior) and ecological (availability and quality of habitats) processes.

Understanding this organization is like understanding how complex systems can work effectively without central intelligence. In this context, the « intelligence » of the marine world is neither neuronal nor intentional. It is collective, spatial and emerging.

Each physical process plays a specific role. For example:

- sea currents form an invisible infrastructure, comparable to a communication network;

- functional habitats, breeding areas, feeding areas or adult habitats, constitute nodes;

- Finally, the larvae ensure the circulation between these nodes, making it possible to connect the system

Modeling invisible networks

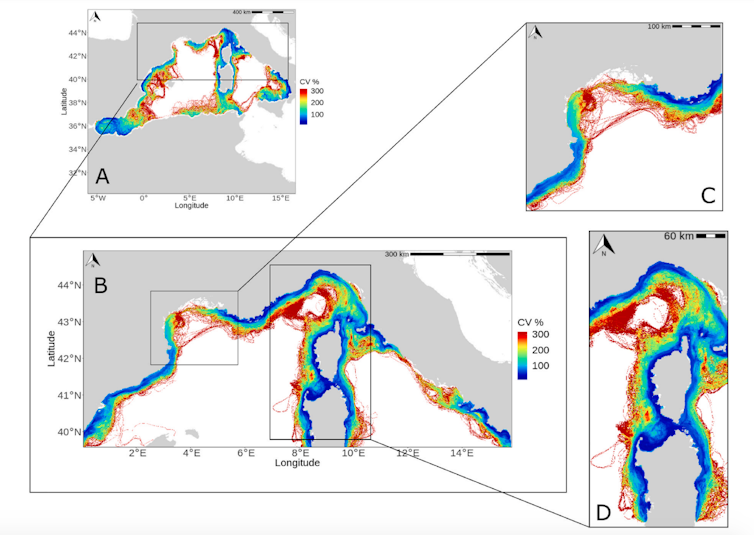

In my work, I seek to model this connectivity, that is, the network of exchanges whose structure conditions the resilience, adaptability and persistence of marine populations in the face of environmental disturbances.

To explore these invisible networks, I use ditslagrangian biophysical models, which combine oceanic data (currents, temperature, salinity) with biological parameters specific to the species studied, such as larval life or reproduction period.

The objective is not to predict the exact path of each larva, but to bring out global structures: dispersion corridors, source areas, isolated regions or exchange crossroads.

This is precisely what I showed in a recent work devoted to the great sea spider Maja squinado in the northwestern Mediterranean. By simulating more than ten years of larval dispersion on a regional scale, I highlighted the existence of real connectivity crossroads. They connect some remote coastal areas, while others, although geographically close, remain weakly connected.

Intelligence based on relationships

This organization is not the result of any conscious strategy. It emerges from the interaction between ocean circulation, species biology and the spatial distribution of favorable habitats.

The results obtained illustrate a form of collective intelligence of the system, in which the global organization far exceeds the sum of individual trajectories.

Here we find properties common to many complex systems – insect colonies, trophic networks or human social dynamics. In all cases, it is the relationships between the elements, much more than the elements themselves, that structure the functioning of the whole.

source : science et vie