In a special issue of Environmental Science and Pollution Research (ESPR) published on April 7, 2025, dedicated to the study of the source, fate, and effects of plastic waste in the European land-sea continuum, scientific discoveries shed light on the invisible pollution of microplastics that crosses borders between ecosystems. This unique compilation of 14 scientific papers highlights major findings from the Tara Microplastics Mission (2019), focusing on the origin and flow of plastic pollution in nine European rivers: the Loire, Seine, Rhine, Elbe, Thames, Ebro, Rhône, Tiber, and Garonne.

All European Rivers are Affected

Rivers are the main pathway for human-made waste to reach the ocean. Each year, they release a staggering 8 to 12 million tons of plastic debris, which accumulates in ecosystems worldwide, posing a risk to biodiversity.

In 2019, the Microplastics Mission studied the origin and flow of plastic pollution in major European rivers. One of the scientific goals was to quantify the density (number of plastic particles per volume unit) and mass (mass per volume unit) of microplastics in the Loire, Seine, Rhine, Elbe, Thames, Ebro, Rhône, Tiber, and Garonne.

Over seven months, a total of 2,700 samples were collected from river mouths, estuaries, and upstream and downstream of the first large cities encountered. Since all samples were taken using the same sampling methodology, scientists were able to compare results from the estuaries of these nine rivers.

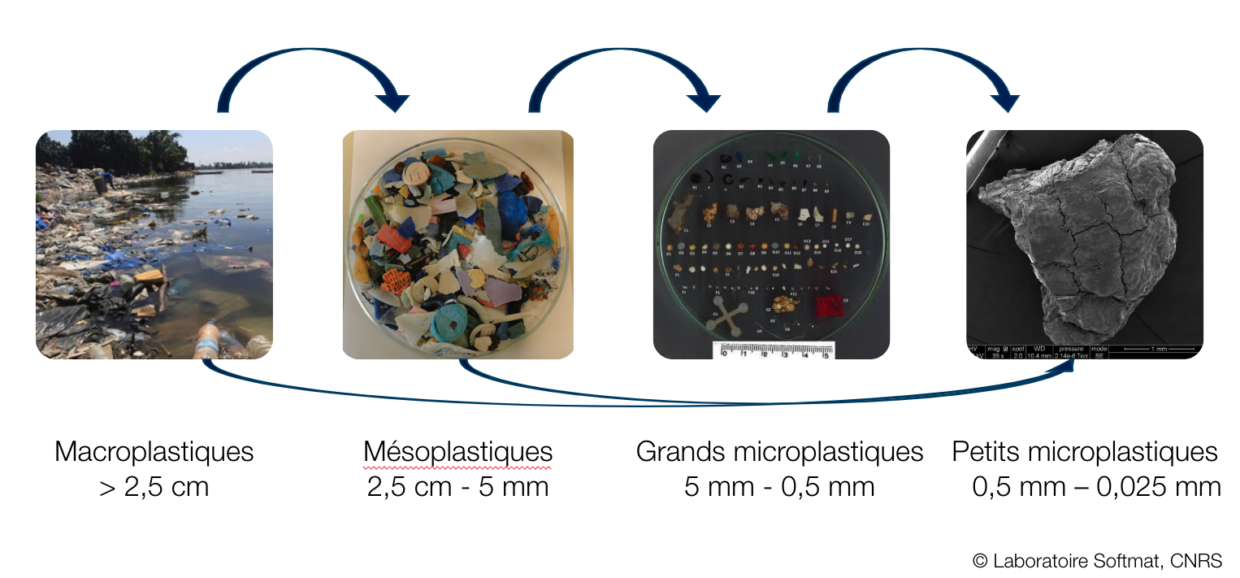

Two sizes of microplastics were studied: large microplastics (between 0.5 and 5 mm) and small microplastics (between 0.025 and 0.5 mm).

The results are concerning: all the European rivers studied are polluted by microplastics.

An Invisible and Universal Pollution

Small Microplastics: Smaller but More Numerous

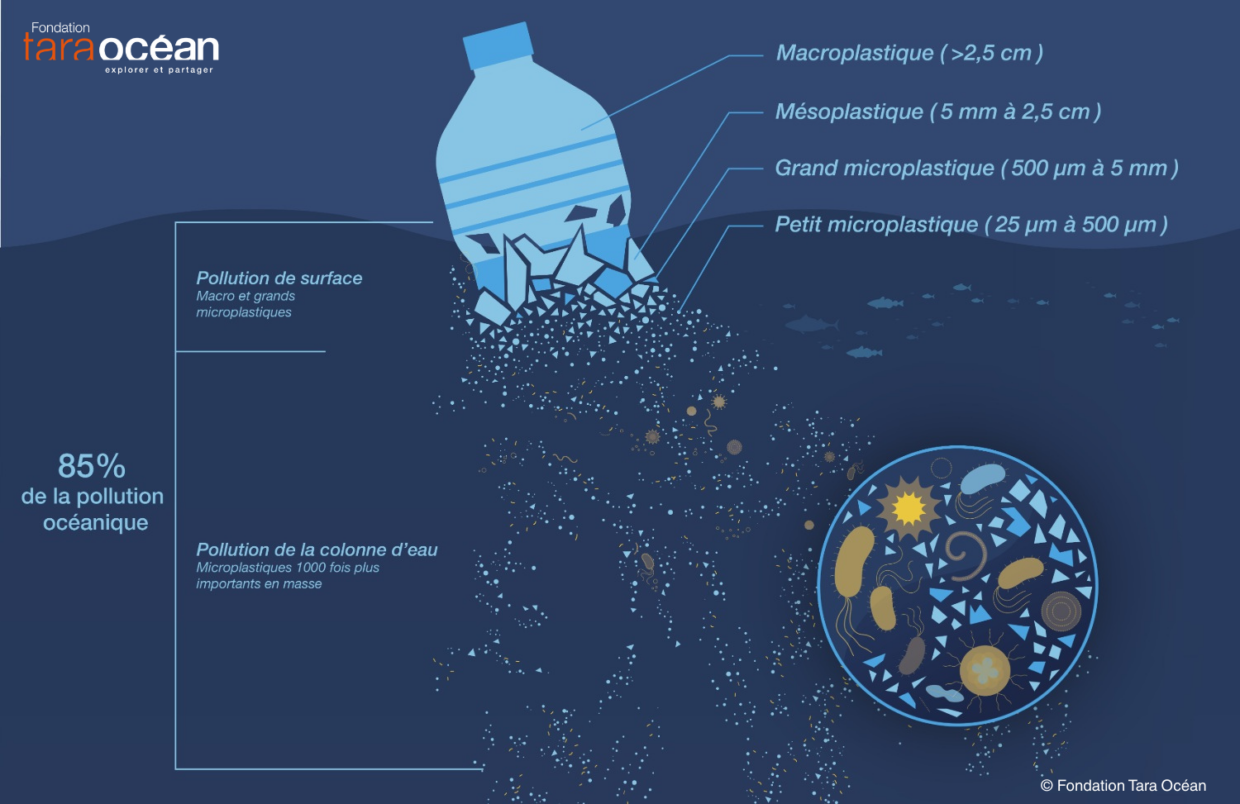

The analysis shows that small microplastics (between 0.025 and 0.5 mm) are up to 1,000 times more numerous and heavier than larger microplastics on the surface of the nine European rivers studied.

These small microplastics, invisible to the naked eye, are far less studied, although these findings show they represent the submerged part of the iceberg. Scientists are particularly concerned about these alarming concentrations in the rivers.

These small microplastics are even more likely to be ingested at all levels of the food chain, from microzooplankton to fish.

This discovery was made possible by advances in technology and precision in analysis methodology, particularly through mass spectrometry after the pyrolysis of microplastics, a system that pushes the limits of the infinitely small and increases accuracy in establishing mass balances.

From the Surface to the Abyss, Microplastics are Omnipresent

No ecosystem is spared.

The Rhône, which has the highest freshwater input in the Northwestern Mediterranean basin, was used as a base for understanding the mechanisms by which microplastics are transported from rivers to the ocean.

3D simulation models were used to assess the dispersion of microplastics released by the Rhône. The study showed that particles propagate across the entire Mediterranean basin in less than a year. Over half of the large floating microplastics are exported to the Algerian basin and further east. Microplastics that sink remain closer to the river mouth, in the Gulf of Lion.

The distribution of small microplastics is much more homogeneous in the water column, affecting all ecosystems from the surface to the abyss.

Urban and Rural Pollution: No Preference for Pollution

Researchers also wanted to know whether the origin of the pollution could influence its impact on ecosystems.

They did not observe any systematic impact from urban areas on microplastic concentrations in water. No major differences were found between samples taken upstream and downstream of the largest cities near river outflows. This may be explained by diffuse pollution, coming from both urban runoff upstream and agricultural lands or the transport of small microplastics through the atmosphere.

A « Pollutant Sponge » Effect and Chemical Threat

The impact of microplastics on aquatic wildlife in rivers and the ocean was assessed by exposing plastic pellets to mussels, which are filter feeders that bioaccumulate microplastics as well as the chemicals they may contain.

The analysis highlights the « pollutant sponge » effect of plastics, which absorb many harmful substances such as heavy metals, hydrocarbons, and pesticides. It also underscores the toxic impact of chemicals added during plastic production, including more than 16,000 additives, 3,000 of which are already recognized as toxic.

The impact of plastics is thus not limited to the chemical composition of the plastic itself but also includes the chemical cocktail the plastic absorbs. It is essential to consider the systemic dimension of plastic pollution (toxic, chemical, and of course, climatic).

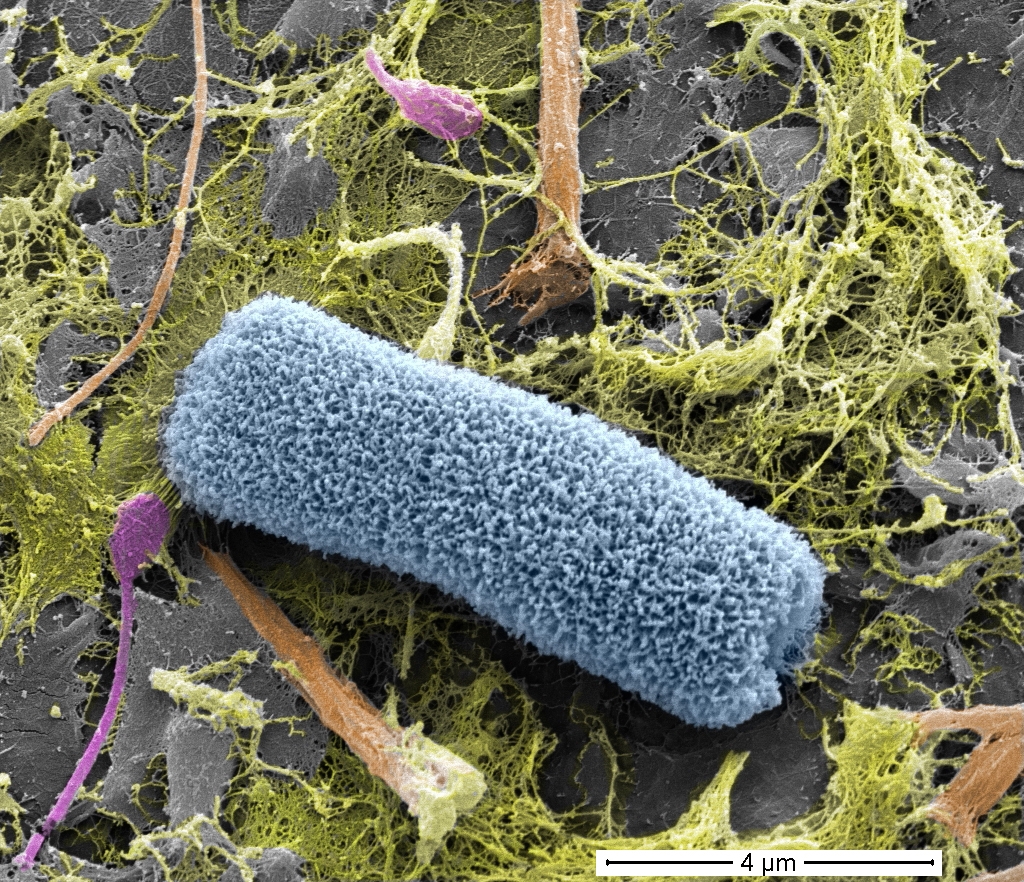

The Plastisphere: A Habitat for Microorganisms, Including Pathogens

« Plastisphere » is a relatively new term used to describe microorganisms living on plastic waste in the environment. Notably, the first pathogenic bacterium virulent to humans (Shewanella putrefaciens) was discovered on a microplastic. This bacterium is responsible for bacteremia, otitis, soft tissue infections, and peritonitis in humans. This study demonstrates the additional danger of the dispersion of microplastics in the environment, which can spread pathogenic microorganisms over long distances. This discovery links plastic pollution to the global health of the planet, establishing a close relationship between environmental health and human health.

These plastic rafts facilitate the transport of microorganisms from one environment to another, thereby extending the environmental impacts of plastic across different ecosystems.

Results Supplemented by a Participatory Science Initiative

A participatory science initiative with schoolchildren, Plastique à la loupe, was also introduced in this special issue. It allowed, for the first time, the comparison of the distribution of various waste sizes (macrowaste, meso- and microplastics) across a wide range of riverbanks and coastal beaches in France.

Reliable data on the distribution, abundance, and types of plastic debris are needed, particularly on riverbanks, which have received less attention than coastal beaches.

The Plastique à la loupe initiative, involving more than 15,000 students per year (400 classes annually), revealed significant plastic pollution in France, primarily from plastic pellets. These primary plastic pellets form the basis of plastic products manufactured by the plastics industry.

This study showed that industrial plastic pellets, also known as « mermaid tears, » make up a quarter of the large microplastics collected from riverbanks and the French coastline. The study also revealed that riverbanks are mainly polluted by single-use plastics, primarily food-related, while coastal areas gather fragmented debris larger than 2.5 cm.

Plastique à la loupe is a participatory science initiative with students led by the Tara Ocean Foundation in partnership with CEDRE, the Microbial Oceanography Laboratory (CNRS), ADEME, and the Ministry of National Education and Youth.

Urgent and Systemic Action is Necessary

These studies highlight the scale of plastic pollution in rivers, confirming large-scale pollution already observed in the oceans. Scientists have shown a direct link between plastic production and environmental pollution. Plastic production has doubled in the last 15 years (from 200,000 to 400,000 tons of plastic produced annually). It is urgent to act to drastically reduce plastic production to limit pollution at the source.

Plastic pollution in the ocean is ubiquitous, with a majority of plastics present in very small sizes, making their removal difficult. This pollution will only increase with the projected tripling of global plastic production by 2060.

Plastics are also significant vectors of chemical contamination. They act as pollutant sponges, accumulating and transporting a cocktail of toxic substances.

Urgent action is needed to integrate the chemical dimension of plastics into environmental regulations. Finally, this pollution represents a direct risk to human and environmental health. The presence of pathogens on polluting plastics establishes a clear link between this pollution and the global health of our planet, threatening the balance of all living things.

It is urgent to act to limit the health impact of plastic pollution, which affects human health and the balance of life.

Source: fondationtaraocean