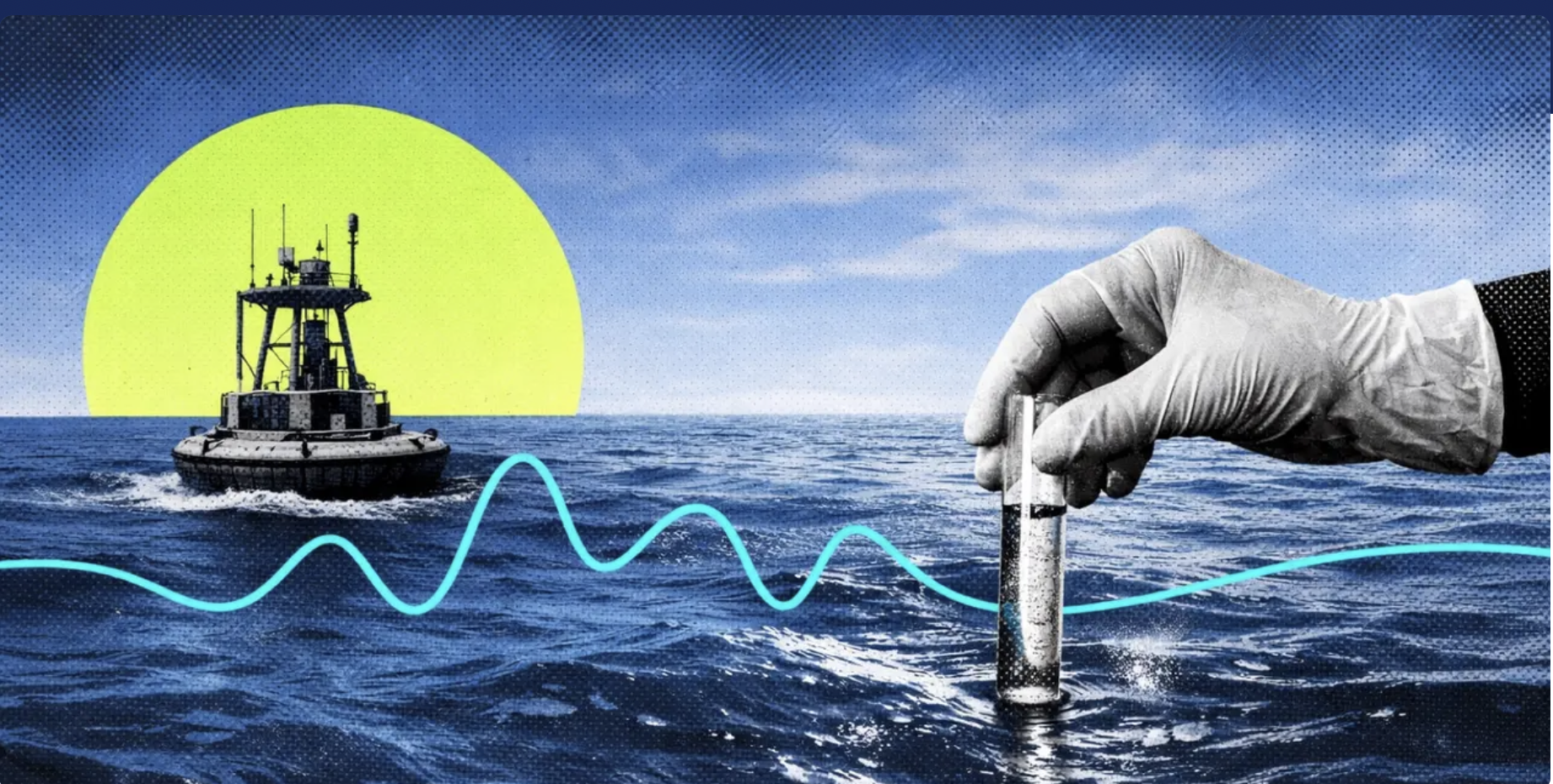

Presented as a providential technological response to the climate emergency, marine geoengineering attracts start-ups, private funds and tech giants, despite still fragile scientific bases. But isn’t the promise also an ecological mirage? By dint of betting on these speculative solutions, don’t we divert attention and resources from the only priority that is worth: the immediate and drastic reduction of greenhouse gas emissions?

The word « geo-engineering » covers a large number of techniques, from the « space umbrella« , which limits the arrival ofLightOfSunin the atmosphere, to the soining of the ocean to make it absorb even moreCarbonthan he does it naturally.

Manuel Bellangerstudies at Ifremer the development of marine geo-engineering techniques with his economist’s perspective. This interview, conducted by Elsa Couderc, head of Science and Technologies, is the second part of « Crossed Views » on climate geoengineering. In the first, we explore with Laurent Bopp,Climatologistand academic, the new climate risks that these techniques could bring out.

The Conversation: Marine geoengineering is poorly known in France, yet it is developing abroad. Who develops these projects?

Manuel Bellanger: With regard to the ocean, theSpectrumof actors and geo-engineering techniques is very varied. The most cautious initiatives are generally led by research institutes, for example in the United States or Germany. Their purpose is rather to understand whether these interventions are technically possible: can we develop methods to capture atmospheric CO2 by the ocean, measure the amount of carbon stored sustainably, verify the statements of the different actors, study the ecological impacts, try to define good practices andProtocols? These research projects are typically funded by public funds, often without an immediate profitability objective.

There are also collaborations between academic institutions and private partners and, finally, at the other end of the spectrum, a number ofStart-upthat promote the rapid and massive deployment of these techniques.

Can we hope to make money with marine geoengineering?

Mr. B.: The business model of these start-ups is based on the sale of carbon credits that they hope to be able to put on the voluntary carbon markets – that is, they seek to sellCertificatesto private actors who want to compensate for theirIssues.

For this, the sequestration must be certified by standards or authorities. Knowing that there are also private initiatives that developCertifications… today, it’s a bit of the jungle, the voluntary carbon markets. And the purchase of these certified credits remains on a voluntary basis, since there is generally no regulatory obligation for companies to offset their emissions

Can you give us examples of such start-ups and the state of their work?

Mr. B.: Running Tide, in the United States, tried to develop carbon credits from algae cultivation on buoysBiodegradablewho had to sink under their own weight into the abyssal depths. But they failed to produce significant amounts of algae. The company eventually resorted to spilling thousands of tons of wood chips into Icelandic waters to try to honor the carbon credits they had sold. But experts and observers criticized the lack of scientific evidence showing that this approach actually allowed the sequestration of CO2 and the lack of assessment of the impacts on marine ecosystems. The company finally ceased operations in 2024 for economic reasons.

A Canadian start-up, Planetary Technology, is developing an approach to increasing ocean alkalinity to increase theAbsorptionof atmospheric CO2 and its long-term storage in dissolved form in the ocean. For this, they add to the seawater of alkaline ore, hydroxide ofMagnesium. They announced that they had sold carbon credits, including toShopifyand British Airways.

The commercial ecosystem is already flourishing in North America, even if we don’t necessarily hear about it here

Another company, Californian this time, Ebb Carbon, also seeks to increase ocean alkalinity, but by electrochemistry: they treat seawater to separate it into alkaline flows andAcids, then return the solutionAlkalineIn the ocean. This company announced that it had signed a contract withMicrosoftto remove hundreds of thousands of tons of CO2 over several years.

The commercial ecosystem is already flourishing in North America, even if we don’t necessarily hear about it here.

There is also a kind of fund, called Frontier Climate, which contracts early for tons of CO2 that will be removed from the atmosphere in the future: they buy carbon credits in advance from companies that are in the development phase and that are not yet really capturing and sequesting carbon. Behind this fund, there are tech giants, such asGoogleOrFACEBOOK, among the founding members. We can assume that this is a way for these companies, which have aEnergy consumptionimportant enough, to buy a climatic virtue. So they have already announced that they have bought for $1.75 million (more than 1.5 million euros) of carbon credits from ocean alkalization companies.

And yet, you said earlier that we are not yet sure to know how to scientifically measure whether the ocean has absorbed these tons of carbon.

Mr. B.: Indeed, the scientific bases of these techniques are really notSolidsToday. We do not yet know how many CO2 they will capture and sequester and we also do not know what the impacts on the environment will be.

And on the scientific side, there is currently no consensus on the ability of marine geoengineering techniques to remove enough carbon from the atmosphere to really slow down climate change?

Mr. B.: There is even practically a scientific consensus to say that, today, marine geoengineering techniques cannot be presented as solutions. In fact, as long as we have not drastically reduced emissions ofgreenhouse gases, many consider it completely futile to want to start deploying these techniques

Indeed, today, theorders of magnitudementioned (the number of tons that companies announce to sequester) have nothing to do with the orders of magnitude that would change anything at theClimate. For example, for the cultivation ofMacroalgae, someModelingestimate that 20% of the total surface of the oceans should be covered with macroalgae farms – which is almost absurd in itself – to capture (if it works) 0.6 gigatons of CO2 per year… compared to the 40 gigatons that humanity emits today every year. If these techniques could play a role in the future to offset the emissions that theGiecdesignates as « residual » and « difficult to avoid » (of the order of 7 to 9 gigatons of CO2 per year by 2050) and achieve objectives ofCarbon neutrality, deploying them today could in no way replace rapid and massive emission reductions.

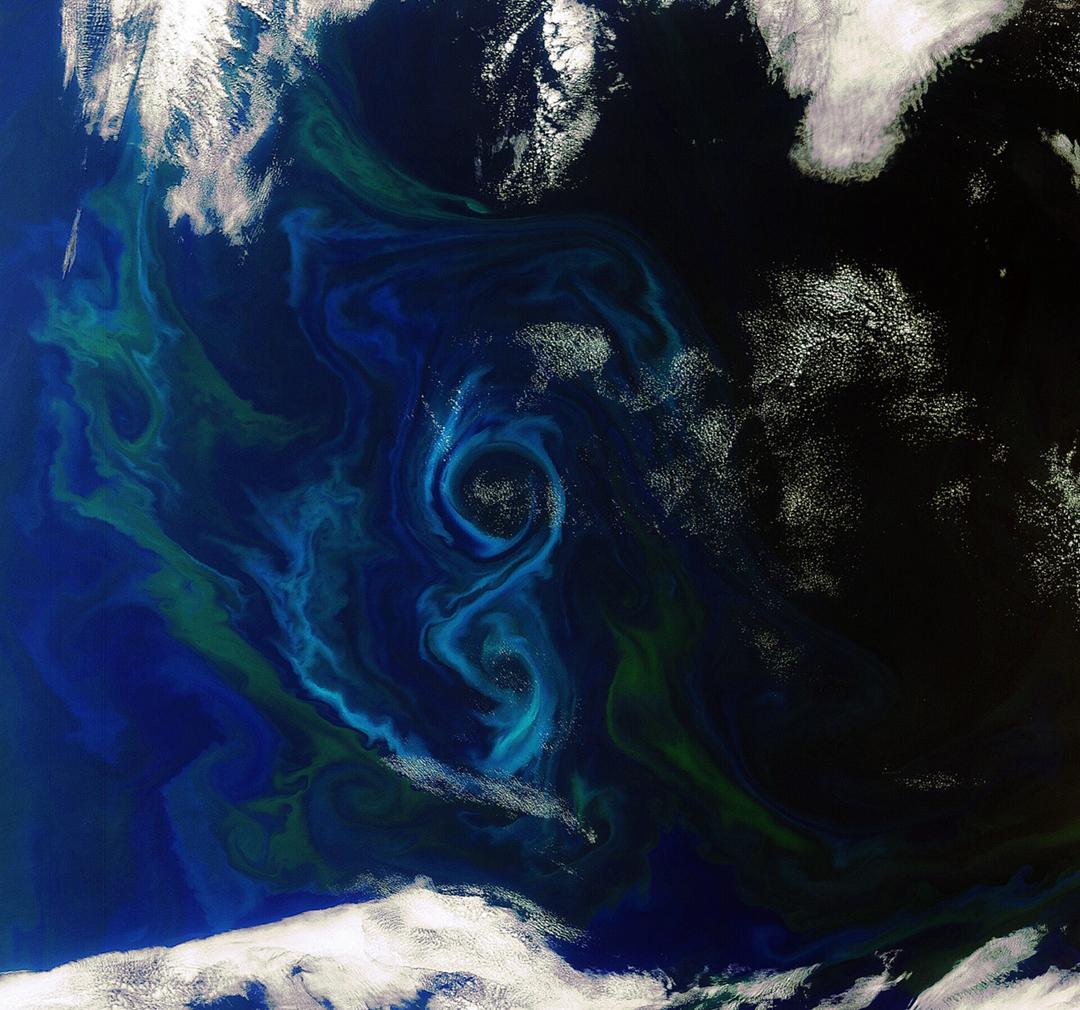

The ocean plays an important role in absorbing and storing carbon in the Earth’s atmosphere. Start-ups seek to promote this storage in order to limit the impacts of climate change, but the effectiveness and risks of these techniques are poorly understood. (In this Envisat image, a proliferation of phytoplankton forms an eight-shaped vortex in the South Atlantic Ocean, about 600 km east of the Falklands). © ESA, CC BY-SA

The ocean plays an important role in absorbing and storing carbon in the Earth’s atmosphere. Start-ups seek to promote this storage in order to limit the impacts of climate change, but the effectiveness and risks of these techniques are poorly understood. (In this Envisat image, a proliferation of phytoplankton forms an eight-shaped vortex in the South Atlantic Ocean, about 600 km east of the Falklands). © ESA, CC BY-SA

So, who is driving these technological developments?

Mr. B.: A number of initiatives seem to be pushed by those who have an interest in the status quo, perhaps even by some who would not have a real will to deploy geo-engineering, but who have an interest in diverting to delay the action that would aim to reduce emissions today.

We think more of fossil fuel players than tech giants, in this case?

Mr. B.: The actors of theFossil fuelshave indeed this interest in delaying climate action, but they are in fact less visible today in the direct financing of geoengineering techniques – it seems that they are more in lobbying and in the speeches that will legitimize this kind of techniques

In fact, doesn’t investing in geoengineering run the risk of diverting the attention of citizens and governments from the urgency of reducing our greenhouse gas emissions?

Mr. B.: It is a risk clearly identified in the scientific literature, sometimes under the name of « climate moral hazard », sometimes a « deterrence effect ». Behind it, there is the idea that the promise of future technological solutions, such as marine geoengineering, could weaken the political or societal will to reduce emissions now. So the risk of being less demanding on our political decision-makers so that they keep climate commitments and, ultimately, that the gap between objectives and real climate action is always greater.

In addition, we have financial resources, resources in labor, in expertise, which are all in all limited. Everything that is invested in research and development or for the experimentation of these geo-engineering technologies can be done at the expense of the resources allocated for known and demonstrated mitigation measures: energy efficiency,renewable energy, sobriety. We know that these solutions work: they are the ones that should be implemented the fastest.

The top priority – we keep repeating it – is the rapid reduction of greenhouse gas emissions. So the position of most scientists is that these marine geoengineering techniques should be explored from a research perspective, for example to evaluate their effectiveness and their environmental, economic and social effects, in order to illuminate future political and societal choices. But, again, today marine geoengineering cannot be presented as a short-term solution.

Mr. B.: States must be strongly involved in the governance of geoengineering, and international treaties are needed. For the moment, it is quite fragmented between different legal instruments, but there is what is called the London Protocol, adopted in 1996, to avoid pollution at sea by dumping (being able to unload things at sea). This protocol already partly regulates the uses of marine geoengineering.

For example, theocean fertilizationby addingIronto stimulate thePhytoplanktonwhich captures CO2 byPhotosynthesis. This technique is part of the existing framework of the London Protocol, which prohibits the fertilization of the ocean for commercial purposes and has imposed a strict framework for scientific research for more than fifteen years. The protocol could be adapted or amended to regulate other marine geoengineering techniques, which is easier than creating a new international treaty

Climate COPs are also important for two reasons: they bring together more nations than the London Protocol, and they are the privileged framework for discussing carbon markets and therefore to avoid the proliferation of uncontrolled trade initiatives, to limit environmental risks and doubtful carbon credit-type excesses.

There are precedents with what happened on forest carbon credits: a survey published by the Guardian in 2022 showed that more than 90% of projects certified by Verra – the leading world standard – have not prevented deforestation or have greatly overestimated their climate benefits. Without supervision, marine geoengineering could follow the same path.

Finally, there are of course equity issues, if those who implement an action are not those who risk suffering the impacts! Here too, there are precedents observed on forest projects certified to generate carbon credits, where economic benefits are captured by investors while local communities suffer restrictions on access to forest resources or are exposed to changes in their lifestyle.

In concrete terms, what are the risks for populations who live near the ocean or use it as a nutritional resource, for example?

Mr. B.: It really depends on the geo-engineering technique used and where it will be deployed. For example, if we imagine a massive deployment of algae crops, it could modify coastal ecosystems, and also generate competition for space with theFishingOr theAquacultureTraditional.

On the coasts, where maritime activities are often very dense, there are already conflicts of use, which can be observed, for example, in the tensions around offshore wind farm installations.

source : futura sciences