With its pirates and deserted islands, maritime imagery is very popular in children’s literature, as are questions about the future of biodiversity and political issues.

In the run-up to the United Nations Ocean Conference (UNOC) to be held in Nice in June 2025, a year will be dedicated to the sea between September 2024 and September 2025. The preservation of the seas and oceans is of interest to all of us, and particularly to the younger generations, which is why we need to take a closer look at the representations in books aimed at them.

In the light of the corpus of books for young people, old and new, it is clear that the sea assumes a variety of functions. Sometimes reduced to a functional role, it is more often associated with political, ecological or ethical issues from a didactic perspective.

Whether written for young readers, appropriated by them or adapted for them by schools or publishers, stories featuring the sea are long-standing, numerous and varied: Les Voyages de Sindbad le marin, Les Aventures de Télémaque, those of Gulliver, Énée, Ulysse , to begin with. The discovery of the new continent and the maritime explorations that accompanied it then gave rise to robinsonnades, pirate stories and other tales of adventure at sea, notably by Jules Verne. Closer to home, it’s Fifi Brindacier who dreams of setting sail, and Maurice Sendak’s hero Max who takes to the sea to board the kingdom of the maximonsters.

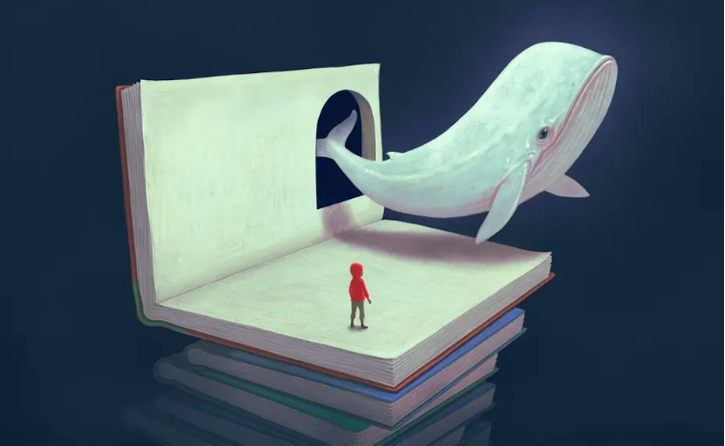

Contemporary representations partly inherit this ancient production, often using it as intertext. These include adaptations and rewritings of great myths such as Ulysse ou de Jonas, as well as the revival of Moby Dick in Roberto Innocenti’s L’Auberge de nulle part or Luis Sepulveda’s Histoire d’une baleine blanche.

A pasteboard decor?

Iconographically, the sea can be represented by a simple blue surface, or white in the case of polar seas, with a play on color as in Coda, petit ours blanc by Rury Lee (where snow protects the bear cub from the hunter) or Esquimau by Olivier Douzou.

Often, however, it becomes a colorful space that calls for exploration by the characters: the aim is to show young readers the seabed that is inaccessible to them, using various techniques such as games as in Lilly sous la mer, 3D vision in Jim curious, Voyage au cœur de l’océan, and stimulating their imagination with sometimes fanciful visions as in David Wiesner’s text-free album Le Monde englouti.

This configuration, which relegates the sea to a role of romantic background or reduces it to a symbolic vacation beach, is particularly present in series aimed at younger children, such as Les vacances du petit Nicolas, Le Club des cinq au bord de la mer, Petit ours brun se baigne dans la mer, Martine à la mer…

The sea is simply a blue backdrop, contrasting with the yellow of the beach, which will be replaced in a subsequent album by another stereotypical space for children’s adventure.

A political space

The political nature of the maritime space is particularly apparent in novels, often aimed at teenagers, that evoke slavery and, in particular, the Atlantic Ocean crossings aboard slave ships, as in Alma by Timothée de Fombelle or Les trois vies d’Antoine Anacharsis by Alex Cousseau.

This critical re-reading of the past, which reveals the underbelly of colonial ventures in a referential or more fictionalized way (as in François Place’s Les derniers géants), tends at the same time to question the relationship of domination with regard to others and nature (which Macao et Cosmage were already doing), and may come into tension with an ancient model of adventure storytelling.

Similarly, the issue of international migration, which has come to the forefront of public debate in recent years, can be found in a number of albums featuring perilous sea crossings, often presented from the point of view of the child migrant characters, as in Là-bas, Méditerranée or La Kahute , which encourage empathy on the part of young readers.

A threatened space to preserve

The environmental crisis also seems to have a major influence on contemporary children’s literature, which is highly sensitive to this theme. These ecological concerns are reflected in various approaches, such as the development of documentary albums like Eau salée by Emilie Vast or Les fonds marins by Chritina Dorner. Their aim is to increase young people’s knowledge of coastal and maritime flora and fauna.

Other albums, such as Animaux des mers et des océans by Renée le Bloas, aim to draw young readers’ attention to the wonders of living things. This well-intentioned approach, which is sometimes very successful from a graphic point of view, needs to be questioned in terms of the representation of the species portrayed. Certain species, such as polar bears and cetaceans, are over-represented, to the detriment of others that are less iconic or “photogenic”

Some books for young readers aim to show the effects of climate change or the threats to the environment through different eco-themes, in formats that vacillate between fiction and documentary, such as the reversible album De l’autre côté de la mer (On the other side of the sea), which shows the global consequences of an oil spill, or Sur mon île (On my island), which deals with plastic pollution and its consequences for wildlife.

While the tone adopted in these books is often serious and prescriptive for young readers, a few albums manage to combine awareness-raising and humor, relying more on children’s reflexivity, such as Dedieu’s Bonne pèche, which evokes overfishing but ends with an amusing punchline that sees the unemployed sailor become an antique dealer, selling all the strange objects he has found in the water over the years, thus implicitly questioning ocean pollution.

For teenagers, there’s also eco-fiction that questions our relationship with nature or projects us into a more or less apocalyptic future, such as Nicolas Michel’s Oxcean.

An initiatory space

Whether political or ecological, the sea is often a place of initiation: similar to the forest of fairy tales, it stands apart and gives the young hero the opportunity to emancipate himself (like the young children who play sailors in Capitaine Jules et les pirates), to mature (as in Robert Louis Stevenson’s L’Ile au trésor). It also shapes personality (as in Stéphane Servant’s L’Expédition, in which sea voyages are a metaphor for life’s twists and turns).

The sea is a symbol of freedom and independence (individually and collectively, in the utopian setting of the island or ship).

The idea that a stay at sea, even in tragic circumstances such as a shipwreck, ultimately leads to self-discovery, the discovery of others and a form of maturation is at the heart of a number of adventure stories and robinsonnades (e.g. Jules Verne’s Deux ans de vacances). The same is true of M. Morpugo’s novel Le Royaume de Kensucké, in which the author renews the themes of the robinsonnade while associating them with ecological concerns by tackling the issue of saving orangutans.

The sea, from which humanity springs, is revisited by every civilization, and the stories tell of the relationship between man and the sea. The monstrous, violent seas crossed by Ulysses and the first explorers were followed by the turbulent seas of piracy, trade, colonial exploration and the great whale hunts. Then came the pleasant beaches of the vacation seas.

Espace éminemment romanesque avec ses îles désertes et ses pirates, la mer inspire parfois la peur, comme tout phénomène naturel qui peut être dévastateur et son mystère a suscité de nombreux fantasmes (du kraken à la sirène). Mais c’est désormais la crainte de sa disparition et de celle de ses richesses qui semble dominer l’imaginaire contemporain. En plein anthropocène, les récits adressés aux plus jeunes témoignent de la densité d’un imaginaire maritime auquel viennent s’ajouter les craintes des adultes qui cherchent à leur faire partager des récits anciens tout en les chargeant de réparer les erreurs commises par les générations qui les ont précédés.

Source: The Conversation