The UN agency is meeting for the final part of its 29th session from July 15 to August 2, at its headquarters in Kingston, Jamaica. On the agenda are two crucial items: the election of the Secretary General – the outgoing candidate is facing various accusations – and the debate on a moratorium on seabed mining, which many stakeholders would like to see implemented rapidly.

The International Seabed Authority (ISA) has no omnipotent power over the regulation of the Zone, the international maritime space. Its core mission is to decide whether or not to plow the seafloor, where the precious metals needed for our energy transition massively lie.

Until now, there hasn’t been much of a queue at the door. Although the riches of the deep have been known for decades, the technical know-how to harvest them is still in its infancy, and so expensive that the profitability of this budding industry is not assured. But dwindling terrestrial resources (subject to debate) and growing demand are accelerating the rush for these minerals. Of the Authority’s 168 member states, a handful of nations and companies – a minority – want to go headlong into the fray. On the other hand, 27 states wish to block all applications for underwater mining permits, while scientists determine the consequences for ecosystems that are virtually unknown at these depths. According to our information, they could be joined by others in the next few days,

A controversial Secretary General

Sitting on the IAMF used to be like sailing on a sea of oil. As the energy transition has progressed on land, the wind has picked up. Against this backdrop, the role of the IAMF has become dizzyingly crucial, and the election of its boss is no longer a mere formality. The current Secretary General, Michael Lodge, has reached the end of his second four-year term and is seeking re-election.

This British lawyer, a specialist in the international law of the sea, has been involved with the IAMF since its creation in 1996. He is an outspoken proponent of seabed mining, and was involved in the early development of regulations along these lines. “I believe that seabed mining is an essential part of an overall vision for a sustainable world,” he assumed before an audience of business leaders in Hamburg in 2018. In 2019, his personal assistant explained that “our journey is to lead humanity through a wonderful adventure, which is to go very deep into the ocean to extract minerals necessary for human activities on land”.

Michael Lodge is now facing a salvo of accusations, relayed in a New York Times article published in early July. In particular, he is alleged to have used the agency’s funds to campaign abroad for his re-election. More broadly, his detractors, led by Germany, have for several years been criticizing his close links with the mining industry. In fact, he appeared in a video clip produced by The Metals Company. In it, he promotes this Canadian start-up, the most aggressive lobbyist in favor of mining.

Lodge has also been criticized for playing a political role in urging diplomats to speed up the start-up of ocean exploitation. The IAMF secretariat is supposed to maintain a position of neutrality and perform an administrative function.

Michael Lodge, Secretary General of the IAMF (right), is received by Kitack Lim, Secretary General of the International Maritime Organization, on October 12, 2021 in London. IMO/Flickr

Opposing him is a Brazilian oceanographer, Leticia Carvalho, who has been nominated by Brasilia to succeed him. This diplomat is currently Head of the Marine and Freshwater Branch at the United Nations Environment Programme. In the past, she has worked within the Brazilian government to regulate the oil and gas industry. Today, she is campaigning for greater transparency in the Authority’s governance and a refocusing on environmental preservation. No woman has yet headed the IAMF.

Approached by the ambassador of Kiribati (a Pacific archipelago in favor of seabed mining), she has reportedly been offered senior responsibilities within the IAMF in exchange for withdrawing from the race. The Kiribati ambassador confirmed to the New York Times that Secretary General Michael Lodge had approved the move.

Michael Lodge, who is no longer supported by his own country but by Kiribati, denies all these accusations. “We encourage member states to take these allegations into account for this major election, as it will define the future of the IAMF and the seabed”, argues Emma Wilson, policy advisor at the Deep Sea Conservation Coalition (DSCC), a federation of some 100 NGOs. The election of the Secretary General is due to take place at the end of the IAMF General Assembly on August 2.

A hastily drafted mining code to regulate exploitation

Other criticisms have been levelled at the IAMF. Firstly, its mandate appears increasingly contradictory in the light of the climate and environmental crisis: the agency is tasked with drawing up regulations, a mining code, to encourage the emergence of a new subsea mining industry. At the same time, it must adopt “the necessary measures to ensure effective protection of the marine environment against the harmful effects that may result from these activities”. Yet many scientists have already warned of the risks to the “common heritage of mankind” should it be altered.

The mode of governance is also contested. It is virtually impossible for a contract request to be rejected: it would require a two-thirds majority in the Council, the 36-member executive body, followed by a majority in the five chambers. All 31 exploration requests have been granted. One of these permits, issued to Poland for fifteen years, concerns an area considered environmentally fragile by the UN Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). For François Chartier, who has been following this dossier closely for many years for the NGO Greenpeace, “it’s time to change the IAMF (…) it’s time to put environmental preservation at the heart of the IAMF’s work”.

Tensions are running high in Kingston. The Assembly, where the 168 countries can express their views, is called upon, for the first time, to pronounce on a general policy. The Council, which is responsible for drafting the mining code, would be obliged to apply it. One of the aims of this policy is to formally respond to the concerns of all those calling for a moratorium or a precautionary clause on mining. “For us NGOs, it’s an opportunity to put in place all the conditions to be met before even considering the launch of the activity. It’s a major step in the history of the IAMF, and the Assembly is going to assume its power,” explains activist and IAMF-accredited observer Emma Wilson.

But time is of the essence: the first operating application could be submitted this year. The AIFM is obliged to respond because the micro-state of Nauru, which is spearheading the development, has activated the “two-year rule” in 2021, forcing the AIFM to enact a mining code to govern these commercial practices. But the code is still far from being completed, even though it was supposed to see the light of day a year ago. Negotiators are therefore “under enormous pressure to adopt this text as quickly as possible”, laments Emma Wilson. “Either the IAMF adopts a completely dysfunctional mining code and mining begins. Or companies can apply for mining contracts, even in the absence of a mining code, and mining begins too. It would then begin in a regulatory chaos and a scientific vacuum. For us, none of these options are reasonable in the context of the environmental crisis.”

The Metals Company stakes its survival on AIFM

NGOs are therefore promoting a third option: a moratorium until the science speaks. This option is being pursued by a group of 27 countries. Its leader, France, has been calling for a “total ban” on exploitation in international waters since Emmanuel Macron unexpectedly took a stand on November 7, 2022. Our responsibility is immense,” Hervé Berville, France’s Secretary of State for the Sea, told IAMF members in Kingston in 2023. We cannot and must not embark on a new industrial activity when we are not yet able to measure its consequences”. France’s two exploration permits are for research purposes.

In its wake, Germany, Costa Rica, Chile, New Zealand, Spain and the Netherlands are promoting a moratorium or precautionary principle, before eventually letting adventurous industrialists off the hook. With five exploration contracts in its pocket, China was seen as a pioneering state in the field. But in May 2024, during Xi Jinping’s visit to Paris, China made a U-turn and is now taking a cautious approach. For Emma Wilson, the explanation for this about-turn is economic: “It’s not yet certain that this industry will be profitable. The declaration co-signed with France, the country with the strongest position on exploitation, sends a very important message.” As for the United States, while it is not a member of the IAMF, it participates as an observer. Former director of the U.S. Oceanic and Atmospheric Observing Agency and member of the White House Climate and Environment Cabinet, marine biologist Jane Lubchenco believes it’s “time to press pause”.

In the opposite camp, a handful of very disparate countries are actively campaigning to scratch the seabed. Leading the way are Norway, Japan, India and four Pacific islands – Kiribati, Nauru, Cook Islands and Tonga. In the Clarion-Clipperton zone, The Metals Company is already ready to submerge robot-bulldozers at a depth of 4,000 metres, capable of collecting huge quantities of polymetallic nodules. These small pebbles contain the key chemical elements used in the manufacture of electrical components (car batteries, computers, telephones, solar panels, etc.): cobalt, copper, manganese, nickel, rare earths (lithium).

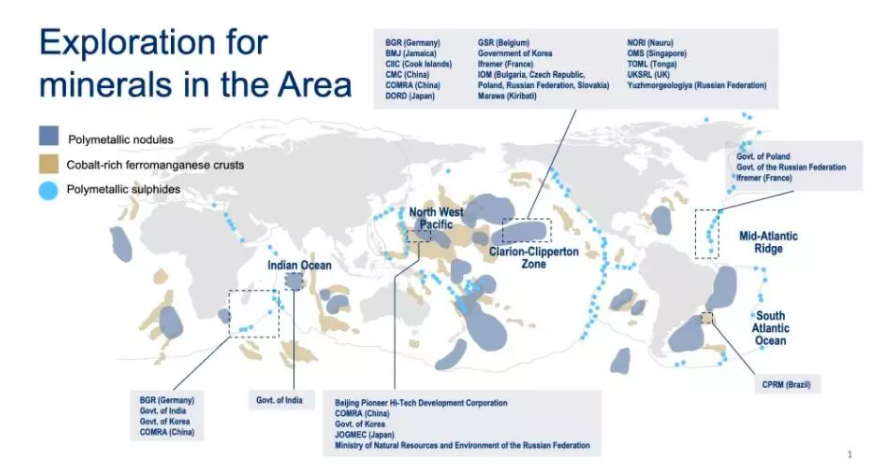

This map from the International Seabed Authority shows the various exploration zones in international waters. To date, the Authority has issued some thirty exploration contracts – none for exploitation – to countries or groups of countries. France has two such contracts, in the Pacific and the Atlantic. IAMF

To defend its aims, this wolf of the abyss plays on the heartstrings of an ecologically and socially battered land surface: “I don’t want to see any more deforestation, I don’t want to see any more child labor. And I want to see us access the most sustainable reserves of these resources”, declared Gerard Barron, its Australian CEO, who lives between Dubai, California and London. “Our latest campaign to assess the state of the ecosystem 12 months after the end of the nodule collection pilot project is encouraging. We believe we now have enough data to address most of the concerns raised by those opposed to the industry,” he says on March 25, 2024.

The Metals Company is staking its survival on the AIFM. While the green light from the UN agency is still awaited, some investors have begun to give up on it, according to the New York Times. With Nauru supporting her politically and holding an exploration contract, she wanted to kick-start the process. Some twenty other companies are said to be ready to operate.

Key commitments to the protection of oceans and marine life have punctuated the last forty years, since the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea. In 2022, the 15th COP on Biodiversity pledged to protect 30% of marine (and terrestrial) ecosystems by 2030. A decision taken by the 196 states meeting in Montreal “encourages” governments “to ensure that, prior to any deep seabed mining activity, appropriate marine environmental and biodiversity impact assessments have been conducted, risks are understood, technologies and operational practices do not adversely affect the marine environment and biodiversity, and that appropriate rules, regulations and procedures are put in place by the International Seabed Authority”. A burning question that is unlikely to be answered any time soon is how the IAMF plans to monitor the operations, which would last several years, 24 hours a day at a depth of 4,000 meters. It’s simply impossible,” replies Emma Wilson. We know there have been breaches of exploration contracts. The IAMF has never sanctioned them. It’s not an effective regulator.”

Many scientists have warned of the irreversible consequences this industry would cause: cascading disturbances in the water column and floor, deposits of foreign elements from ships, dispersal of million-year-old sediments, disappearance and alteration of species from the food chain, habitats and ecosystems, or light pollution and noise nuisance from a dark, silent universe.

For example, according to a 2020 scientific study cited by the DSCC, if the 17 exploration permits currently in force in the Clarion-Clipperton zone were to become as many authorizations to mine, the work sites would have a geographical impact equal to the surface area of France. Another risk lies in the release of greenhouse gases stored deep underground. The ocean is the planet’s main climate regulator and carbon sink.

Source: Rfi