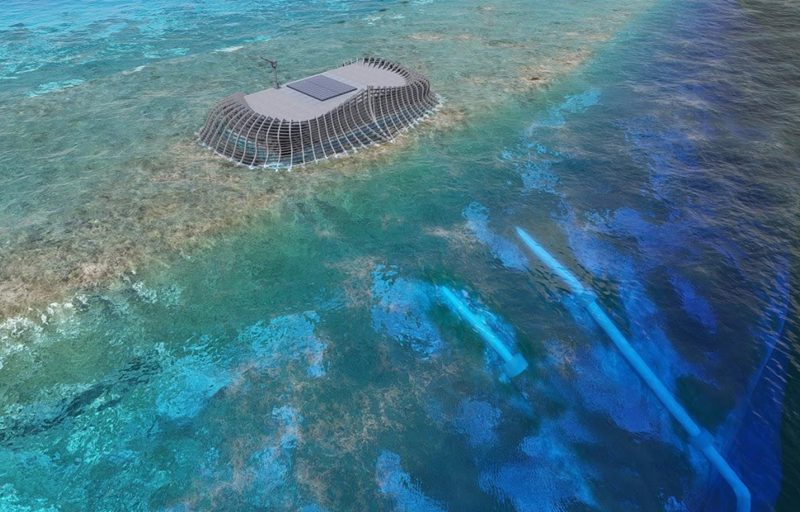

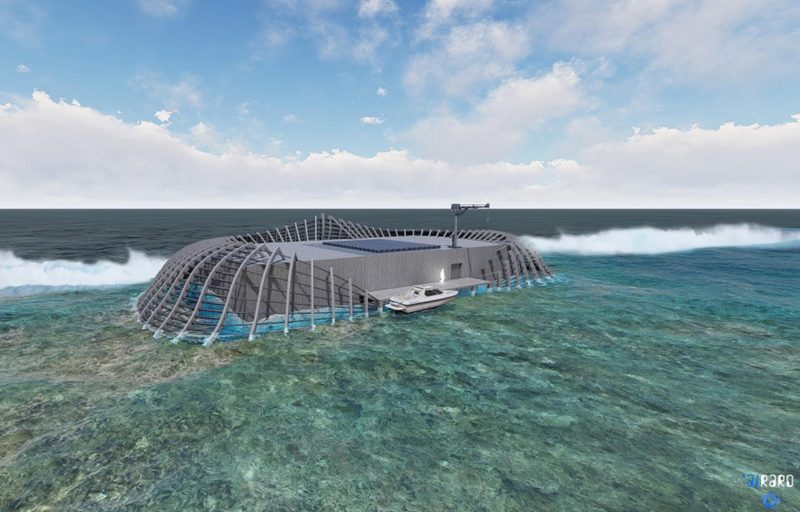

While the country reaffirms its commitment to supporting marine energy, the local company Airaro claims to be technically ready to move forward with a first commercial production unit for OTEC (Ocean Thermal Energy Conversion). Known for its expertise in SWAC (Seawater Air Conditioning), the company believes that, despite being at the center of many unrealized announcements over the past 20 years, this technology remains « the only one that can provide clean, constant, and guaranteed energy » and help achieve « more than 50% renewable energy. » Installed on a reef after a final phase of « industrial optimization, » the unit could generate 8% of Tahiti’s electricity.

It’s an idea that has been long discussed—these monstrous, or at least ambitious, projects that have inhabited conversations for too long without seeing any tangible progress. Nearly 20 years have passed—and that doesn’t even count studies from the 1980s—since Ocean Thermal Energy (OTEC) reappeared in Polynesian discussions. This includes talks from local autonomists, independents, the state, and local or international developers… We can mention, among others, the discussions, contacts, and even commitments from the Temaru, Tong Sang, and Fritch governments on the subject, projects from the Moux Group, partnerships with Japanese researchers, and the ambitions of the French group DCNS, now Naval Group, which made several announcements on the topic in Paris or Papeete before letting its specialized subsidiary fall silent.

Despite the repeated announcements, agreements, and subsidies that led nowhere, the idea of bringing this technology, which harnesses the temperature difference between surface and deep waters to generate electricity, to Polynesia has never disappeared. Last year, Moetai Brotherson once again discussed potential « cooperation » on OTEC with Japan. His government also officially stated in its Sustainable Blue Economy roadmap its intention to « support the development of marine energy projects, » « evaluate the feasibility of electricity production from ocean thermal energy, » and « support demonstration projects. » Warren Dexter, the Minister of Finance in charge of Energy, confirms today that the movement is underway and that the administration should be mobilized in the coming weeks to make these commitments a reality.

« No R&D Needed for Theory, Just Industrial Optimization »

While private developers are much quieter internationally than in 2010 or 2015, a local player, Airaro, is looking to push the authorities forward and is more than ever claiming that OTEC is ready to advance. This local consulting, management, and project development company, specializing in marine energy, is best known for its expertise in SWAC, developed from Bora Bora to Taaone and Tetiaroa. SWAC itself was once viewed as a pipe dream, but now Airaro is in the process of exporting it worldwide from Polynesia. OTEC, developed in the 1930s by French engineer Georges Claude—also the inventor of the neon tube—is the « mother technology » of SWAC.

« SWAC is half of OTEC, » summarizes Jean Hourçourigaray, CEO of Airaro. Instead of just pumping cold water from 800 meters deep to run air conditioning circuits, it’s also about pulling hot surface water. The temperature difference allows a fluid—ammonia, kept in a closed circuit—to change state, and following the reverse mechanics of a refrigerator, to generate electricity. This system, naturally more complex to implement than to describe, is something the company says it can now master from start to finish. « There’s no more R&D to be done on the theory, only industrial optimization, » insists Hourçourigaray. He reminds that Airaro worked with DNCS from 2012 on the development of OTEC and has had a « viable and validated model by independent experts » since 2017.

No doubt for the CEO: Polynesia can be a « showcase » for this technology, just as it has been for SWAC. Tahiti has a « clear competitive advantage. » « The fact that cold water is very close to the coast, that our drop-offs are very steep, that we have far fewer cyclones than elsewhere—and we’ve seen recently the damage cyclones can cause—and that electricity prices are very high means that the OTEC solution we’re promoting will be economically and energetically efficient, » adds the co-founder of Airaro, alongside David Wary. Polynesia has the opportunity to be a « global pioneer » of a « new industrial sector. »

Guaranteed Power, Day and Night

« We are ready, » that’s the message to the authorities. Airaro doesn’t want to develop a « demonstrator, » as mentioned in the Blue Economy roadmap, but rather a « first commercial unit » of 5MW. This power isn’t to be compared to the 5 or 10 MW « peak » of recently commissioned solar power plants in the Presqu’île. The electricity produced will indeed be more expensive than photovoltaic— »at the cost of the Punaruu plant’s production, » about 30 francs per kWh versus 18 to 21 for the recent solar farms—but OTEC is a « permanent renewable resource, providing guaranteed power 24/7, 365 days a year, whether it’s cloudy or dark, » emphasizes Airaro. These 5MW could thus provide « up to 8% of the electricity consumed on the island of Tahiti. » « This technology is what will help us reach more than 50% renewable production in our electricity consumption, » insists Jean Hourçourigaray.

480 Million for the Final Industrial Test, One Billion for a Production Unit

However, there’s still one essential step of « industrial optimization » to take before launching the project. To determine the exact output of this production unit « to the nearest kWh, » Airaro wants to build and test in a factory the heat exchanger of the future OTEC unit, a large 12-meter titanium part that ensures heat transfer within the unit. Measurements that can’t be modeled on a computer and that come at a cost: more than 477 million francs, including studies and the part itself. The CEO assures that national financiers, like BPI, are ready to invest three-quarters of these funds in the name of the French industrial revival. But it’s up to Polynesia to take the lead, with « clear » political and financial support. And this isn’t just a gesture for science: for Airaro, OTEC is the only renewable lever that will help reduce the diesel production at Punaruu and take further steps toward the energy independence so often promoted by politicians. « It’s the solution to move from speeches to action, » emphasizes Jean Hourçourigaray.

As for the timeline, Airaro estimates that testing the exchanger in the factory will take 18 months, after which everything will be ready to present the project to investors. « We know they will be numerous, » explains the company’s co-founder, already highly sought after for its SWAC expertise. With a power purchase agreement in hand, private funds will then need to take over—estimated at 9 billion francs according to initial estimates—to build the OTEC unit in three years. A project that, if launched, might spark some debate, as the unit must be built on a reef, ideally Teva i Uta, which is well protected from cyclones. But for the project developers, its impact will not be greater than that of maritime works like the quays in the Tuamotus and will have an obvious long-term environmental benefit.

While Polynesia is still deciding its position, other international players are moving ahead. After signing an initial agreement to develop a project in São Tomé and Príncipe, the British company Global Otec (Ocean Thermal Energy Conversion, the English name for OTEC) and several European partners announced in March the launch of an experiment in the Canary Islands. A territory that has far less potential for ocean thermal energy than Polynesia. Competing projects, SWAC also had many. But it’s in Polynesia where it was born.

Source: radio1